Memories of

David Foster Wallace.

An interview with David Foster Wallace can be found here.

My mom has been in this David Foster Wallace book group for years. A few years ago, she got breast cancer for a second time. At some point during her treatment, she received a postcard from David Foster Wallace saying that a mutual friend had told him that she was sick, and that she was in his thoughts and prayers. He added that one of his favorite words was “abide.” That touched all of us so deeply. We never even found out who the “mutual friend” was.

After she got better, I wrote him a letter thanking him for his kind words. I didn’t need or expect him to write back. Of course he did, wishing again that we were still OK. I think these small gestures show what a sensitive and caring person he was. He will be missed.

— Lilly de Lucia

I had a chance to see David Foster Wallace onstage at a Portland Arts and Lectures event about 10 years ago. He appeared with Sherman Alexie, Gish Jen, and Cristina García as part of a panel discussion on what it meant to be a young writer in America. The event was a large one—probably 1,500 people. It was held in one of those elaborately refurbished downtown movie palaces. Everyone onstage and in the audience was, to some degree, gussied up for the occasion—everyone except Dave, that is. He arrived wearing a pair of big blond work boots, ratty jeans, and some sort of long-sleeve, waffle-weave undershirt. He looked like a down-on-his-luck logger.

There was little reading that night; it was mostly a Q&A. Something Dave said about his nervousness and the peculiarity of the affair made me think of an old Kurt Vonnegut anecdote.

Vonnegut was giving a speech he was nervous about. He didn’t think it was any good. He mentioned this sotto voce to the eminence sitting on the dais beside him and this man told him, by way of reassurance, that he, KV, shouldn’t worry about it—nobody really cared anything about what he had to say; they were just there because they wanted to see if he was an honest man.

When I got home, I wrote Dave a note, passing this little story on. I introduced myself and explained that I had just seen him “flamboyantly underdressed” at the Arts and Lectures event in Portland.

A few weeks later, Dave wrote back. He used a small thank-you card (Expressions from Hallmark). He said he understood Vonnegut’s unease. “These ‘writerly’ forums are a priori impossible to be honest at.”

In a postscript, he replied good-naturedly to my comment about his appearance. He wrote, “I was not underdressed. The lady said casual—the other three were overdressed.”

Given the demands on his time and for his attention, this thoughtful, funny little note to a complete stranger struck me as a surprising and generous thing. From reading these posts, it is obvious that it was not unusual.

— K.B. Dixon

Here is what I think I know about David Foster Wallace: He was humble when he had every right not to be; he was a genius who didn’t ask to be; and he was graced with a piercing self-awareness.

Here is what I am sure I know about David Foster Wallace: He took time to sit down with a self-important pupil and told him to strive to be more authentic. He meant it as a critique of my writing, but I have always taken it as a life lesson. And, as much as anything else has in my life, it has helped.

— Brian Atwood

When I read A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, I decided I wanted to be him. He was so funny, so smart. I was more than smitten. I almost fell off my chair when, during the first week of my postcollege internship at the Boston Review, I learned that my fellow intern, Chrissy, was one of his students at Pomona College—and he’d written her recommendation. What was he like? How she described him was as a goofy man, a guy who, when the class got into a heated discussion, would pause to slap a fresh nicotine patch onto his arm. When he’d prop his feet up onto his desk, you’d sometimes see discarded nicotine patches stuck to the bottom of his shoes.

That summer, he did a reading from Oblivion at a church in Harvard Square. James and I went and had planned on meeting Chrissy there. We found a spot in a pew, and Chrissy snuck in a few minutes after he’d already started to read. He noticed her and stopped midsentence: “Oh, hey, sorry. I just noticed one of my students in the audience. How are you?” I did not know him, but at that moment I knew without a doubt that he was a good teacher and a genuinely kind man.

To me, David Foster Wallace symbolized the possibility to be great. He inspired me and he will continue to be an important influence in my life. I cannot thank him enough.

— Rasika Welankiwar

I obtained Dave Wallace’s address through mildly illicit means to send him some of my early mini-comics. Although he alluded to dark reprisals that were even then on their way to the person who’d passed his information on to me, he was willing to excuse the indiscretion because “these comix are extremely extremely fucking good.” He sent me a check for a subscription, which I don’t believe I ever cashed. I sent him each new issue. In response to one, he wrote that he and his girlfriend had laughed so hard they “got all adrenalized and lost sleep,” which, as you can imagine, was very pleasing indeed.

We corresponded intermittently, by which I mean I wrote him effusive, confiding letters and he wrote cordial, friendly notes or postcards in reply. Now and then, he’d include a little doodled face alongside a note saying something like “You aren’t the only artiste around here, buckaroo.” Once, there was even a self-portrait, with a grossly elongated nose and buckteeth.

Obviously, our slight and mostly unilateral personal connection isn’t the main reason his death has shocked and upset me so. Just as, when I first read him, I thought that here was exactly the writer I would be if only I were much smarter, and a much better writer, reading his more recent work I felt that David Foster Wallace was the person I would be if I were less intellectually lazy and more honest and conscientious, kinder and truer to myself. His authorial voice is always in my head like a conscience, reminding me when I forfeit fairness for humor or compromise my intellectual integrity for a good punch line. Now that he’s gone, I feel like I have to try harder.

— Timothy Krieder

In 2000, when I was a student at Kenyon College, Wallace gave an evening reading on campus. The book-jacket photos fed expectations of a casually cool figure: long hair and a bandanna, perhaps a subtly ironic T-shirt. But in person he looked more like a computer programmer than a celebrated novelist. The way he delivered the material that night—with limited eye contact, standing hunched over and clutching the stapled pages—reinforced this impression of an unassuming, self-effacing man. He seemed, simply, kind.

He read a typically strange and intriguing story (a work in progress) about a boy who was attempting to touch his mouth to every part of his body. When he finished the reading, Wallace positioned himself on a sofa in the refectory lounge, where he signed books for a small group of admirers. It would be a stretch to call it a carnival atmosphere, but the mood was far from staid: At one point, a willowy redhead brought her ankle to her mouth and kissed it.

Someone wanted to know if he still watched Baywatch, as had been reported in the New York Times. “It’s not like I watch it for the boobs,” he said.

As a joke, I had him fill out one of the campus dining-service comment cards. In block letters, he wrote: “Loved the cod! More breading!” To his signature, he added a doodle of a man’s face with a long nose.

Late he sat with us at a long table at the Cove, Kenyon’s dingy on-campus bar with a pirate theme. Wallace ordered a large Coke and took out a stick of gum. Sensitive to our anxieties and aspirations, he talked of how keenly his own students felt the gulf between the published and unpublished. “You’re here, probably, because you’re interested in writing,” he said. “It’s a mixed blessing, finding success when you’re young. If you aren’t published until you’re 40, then you’ve been through the fire.”

Two of us walked him to the bookstore in downtown Gambier. Night had long since fallen, and the guest of honor had forgotten where his accommodations were. Gambier, Ohio, is a picturesque enclave of white picket fences and looming trees where, during the day, the Amish often park their horse-drawn buggies and sell pies, jams, and quilts. On that nightsave for the light in the bookstore—there were few signs of life. We pointed to the Kenyon Inn at the end of the street. The author thanked us warmly and ambled off into the dark.

— Joel Rice

In 1992, I was in Montana working on an MA in literature. A friend of mine was president of the creative-writing club and invited David Foster Wallace to come speak. There was no budget for this club, so DFW stayed at my friend’s house.

After his reading, we went grocery shopping for dinner—the others picked out fixings to make pizza while DFW and I picked out ice cream. I don’t remember what kind we ate or how dinner went, since that night mixes with lots of times like it in grad school, when I ate Gouda and drank microbrews and made witty remarks and stepped around big dogs all night with these smart friends.

After dinner, we watched A Clockwork Orange. I think DFW was somewhere else in his mind. Near the end, he got up without a word and wandered into the hall. In a minute, we heard the shower running.

Years later, as I read through the end of Infinite Jest with confusion and greed and satisfaction and wonder, there was A Clockwork Orange, driving some scenes too spiritually grotesque for me to imagine that they came from that young man who so quietly stood up to take a shower. I don’t try to imagine what was going on in his head that night, just how much of it was there.

Even more years later, I attended a book event for A Supposedly Fun Thing, where I thought I’d reintroduce myself to him and maybe take him out for some sushi. But he read so modestly, so quietly, and answered questions so patiently, and I remembered that I didn’t know him at all.

— Shelly Cox

I played a tennis match against him when I was in the fifth or sixth grade in Urbana, Illinois. He was a better player, and at match point against me I knew I hit the ball out. I went to the net to congratulate him, but he stood there on the baseline and said, “What are you doing? It was in.” I liked that. He just wanted to keep playing.

I lost track of him and, years later, picked up his first collection of stories. And then a collection of essays. Then more stories.

He did something very few people in the world are ever able to do: He made everyone smarter. He took snapshots of our brains, our interior footnoted realities. He made us see that there was always more to say, and ways to say it better.

— Randall Hurlbut

I took a graduate creative-writing course with David Foster Wallace at Illinois State University in 1995 and talked with him occasionally in 1996 when Infinite Jest came out. He had a big influence on my writing, and my favorite story of his, “Good Old Neon,” hit me like no other piece of fiction has—I had this amazing feeling of being interconnected with all life after I read it.

I was not successful with fiction at ISU, but the fact that he (as a faculty adviser for the ISU literary journal Druid’s Cave) liked a poem of mine helped move me toward writing and publishing poetry. His work went to some pretty dark places, and he wrote the best story I’ve ever read about depression (“The Depressed Person”).

In the class, he spoke about addiction and success, how it can eat someone up if a person writes purely for fame and money. He brought in Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet and talked about the capacity of a reader to accept metafictional gimmicks if the prose is good enough. He wanted to write for the right reasons, to hit true feelings rather than just be ironic and funny. I hope that, wherever he is, he is at peace. He has had a giant influence, on writing and on the world, that won’t soon be forgotten.

— Don Illich

I was lucky enough to be one of David’s students at ISU; he was the director of the thesis that finished my degree there. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that his influence changed my life’s direction, and I have no doubt that without his encouragement and support I would have returned to my old job instead of continuing to write and teach. When I began studying with him, though, I was more than a little intimidated. I almost immediately saw that his person/writer ratio was much more person and less writer, which sounds obvious but was both comforting and surprising to me at the time. He was real, to an intensifying point. Even though we hadn’t been in touch lately, he’s still the voice in my head that tells me to try to write something original, interesting, and different, or don’t even bother.

I remember him being kind of a private person, but there is one thing to share, because it made me smile during this sad time: Dave could do the most oddly accurate impression of Mary Tyler Moore saying her famous “Oh, Mr. Grant!” line from her old TV show. It was hilarious, complete with wringing hands and eyes toward the sky.

Although he was brilliant and incredibly generous and honest in the kindest way, he could also be wicked funny. I’ll miss him very much.

— Amy Havel

At public readings, Wallace was funny and polite. He was self-effacing, even when it was clear he was the sharpest cookie in the box. He had a tendency to accelerate when he readevidence, I think, that he was sure of what he had written, that though the sentences were often long and full of all sorts of Faulknerian qualifiers and subordination, he had wrangled his ideas from the bush and captured them, for us, with words that best showed their plumage. I mean to say that, contrary to some perceptions, he was easy to follow.

At one reading I attended, he stopped and apologized for this reading acceleration and said he would try to slow down. We shook our heads and implored him to just please keep reading already. As he signed the new Oblivion and my old Infinite Jest, I thanked himnot for the signatures but for his writing, all of it. In the face of an idol, I didn’t want to sound idiotic or sentimental without cause, but I told him how IJ’s footnotes sent me home from the video store with armloads of Tarkovsky films, how I spent weeks reading the novel commuting on the T.

He thought about it a second, then said, “That’s probably a perfect place to read it. I wrote a lot of it on the T.”

“Ah,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said.

Whole worlds.

When I got home, I checked the inscription. In all caps, with faux pomposity, yet insistently, he had written: “”-1">THE DF LIVES!"

Amen.

— Chad Willenborg

The earliest issues of McSweeney’s are smeared and grubby with David Foster Wallace’s intricate fingerprints. My contributions were no exception to that. The first few issues had footnotes, and diagrams, and discursive digressions, and acrobatic culs-de-sac—and an unrelenting hypersincerity that was then so often mistaken for irony. Also, like David Foster Wallace’s writing, the magazine was often as funny as it was knowing. Eggers had called for cartoons that would be described rather than illustrated, and my friend Jason Zengerle, a New Republic writer and David Foster Wallace fan, contributed the following (uncredited) story, reproduced here in its entirety:

PICTURE:

A high-rise Chicago housing project. Two white men with clipboards are walking in a courtyard. Above them, two black women are looking down at them from a window. One of the two women is pointing.

CAPTION:

“Look, Florence, it’s dissertation time again.”

One day, Adrienne Miller told me that David Foster Wallace was actually teaching Jason’s cartoon in his fiction class, and when I passed along the good news, Jason—who’d had David Foster Wallace sign his galley of A Supposedly Fun Thing with the sheepish caveat “Typo alert!!”—was over the moon.

And then there was Meg McGillicuddy. For the first issue of McSweeney’s, I did a back-of-the-book catalog page, modeled after the kind you would see in the back of a Hardy Boys book. On this page, I wrote about the adventures of Meg McGillicuddy, a 10-year-old sleuth in Chuck Taylors with a magnifying glass and a missing tooth, and listed about 40 different Meg McGillicuddy adventures that you could order (e.g., Meg McGillicuddy and the Cracked Valise, Meg McGillicuddy and the Gym Teacher, Meg McGillicuddy and the Stolen, Hidden Treasure).

After the first issue came out, we got a letter from Bloomington, Illinois. Inside was the page copied and folded, and on the order form, three Meg McGillicuddy titles were circled in red ink. The letter was from David Foster Wallace.

When I read Jason’s New Republic blog entry last Sunday, describing his reaction to the “heartbreaking, stomach-punching news,” I was hoping I was reading him wrong—hoping that Jason’s “DFW, RIP” was meant, somehow, metaphorically. Of all the loving tributes I’ve been reading on mcsweeneys.net this week, the common thread seems to be David Foster Wallace’s generosity, his inability or unwillingness to feel threatened by a crop of younger writers who obviously hoped a footnote or two from his stylebook might rub off on us—and his willingness to encourage us, even indirectly, to leap past our inhibitions and dive in. More than a writer, he was just a brilliant teacher, on and off the clock, on and off the page.

—Todd Pruzan

By the time I first met David Foster Wallace, I was part of the swaying mass of those who idolized him. He was my hero, the person I aspired to be. Still is. But I caught him on a bad day, at an event he didn’t want to attend, discussing business he’d rather not have bothered with. We had a brief exchange and he was somewhat rude to me. I was crushed, confused. My wife and my brother saw this happening and they could see the tears of disillusionment creeping into my eyes, but I defended him! He’s really not like this! He’s a nice guy, I swear! He later e-mailed me a wonderful apology and sincerely felt bad for “snarling” at me. He sent me a beautiful card for my wedding and again apologized and offered heartfelt good will on the marriage. So, even when he was rude (and he was human), he took responsibility for it, truly felt bad for it.

When I discovered Wallace’s writing and Infinite Jest, something resonated in me unlike anything else before or after. I felt in his work a consistent ringing of Truth, a Truth that marries postmodern intellect and sadness with heartwarming humanity. Now my heart is broken, but I take consolation in the fact that his art will live on.

—Matt Bucher

I’ve owned three copies of Infinite Jest. The first copy went missing when lent to a friend. The second copy was, believe it or not, a mass-market paperback found on a bargain table. I remember rereading it in the summer of 1999, while doing fieldwork in the western Aleutian Islands. The binding could not, of course, sustain the weight of the text and Copy Two soon fell to pieces. The third copy is the trade paperback that I still own. When I opened it in search of a few passages yesterday, two bookmarks fell out—one from the main text and the other from the footnotes.

I once had a vivid dream of owning a chocolate Labrador retriever named Hal Incandenza.

Since buying my house, in May 2008, I have thought of the essay “The View from Mrs. Thompson’s” every time I’ve pulled out my lawnmower.

I saw DFW read selections from Oblivion in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was only a few days after I’d fallen down the stairs at work and I was nursing a rather swollen sprained ankle. Because of the crutches, I was slow to make it to the signing line, and ended up bringing up the rear. It was hot and there was no air-conditioning. I was knitting an intentionally ugly sweater out of extremely ugly yarn from the 1970s, and the guy in front of me in line joked that I should tell DFW that the sweater was for him.

Having spent years of my life as a bookseller, I’ve met quite a few authors, but none I admired so much as DFW. I was a little worried that meeting him would diminish my opinion of him. I only spoke to him for about a minute, and I could tell he was exhausted, but he was genuine and kind. He signed my copy of Oblivion “To Ellen—thanks for hobbling to the reading.”

Last night, when looking for a passage in which Kate Gompert describes depression—the only written description that has ever captured my own demon—I began to sob. My dog woke from his gassy slumber and bounded into my lap to lick the tears off my face. I can’t stop thinking about his dogs.

—Ellen Knowlton Wilson

“Mr. Squishy” originally ran in McSweeney’s No. 5, under the pseudonym Elizabeth Klemm. When Dave sent it to me, he asked that this pen name be used, and for the life of me now I can’t remember why. I didn’t even question it, really, because we had already published a bunch of stuff in the journal under other authors’ pseudonyms, and I knew there are plenty of good reasons to occasionally write under a different name. We wanted of course to publish it under his given name, because the story was brilliant and was the longest DFW story we ever got hold of. We were so proud to publish it, but we respected his wishes.

This was the first and only piece we ever published that I attempted to edit. And it was a pretty basic thing I tried to do. His work, as everyone knows, was very difficult to edit, because he made no mistakes, really, and could outthink and outlast anyone when it came to debating changes to his work. It wasn’t that he was combative, but more that he had thought pretty much everything through, and had good reasons for every comma.

Which made it all the more surprising that I got him to break up a few paragraphs. I didn’t think I had a right to ask, but, at the same time, I wanted people to read “Mr. Squishy,” and I felt that some of the paragraphs were both very long and possessing some pretty comfortable places to start anew. So I wrote a note explaining all this, with a copy of the story indicating about 10–15 places we could start new paragraphs.

I didn’t expect him to even entertain the notion, but he did. What became relatively clear in our exchange was that he hadn’t really ever considered breaking up these or any long paragraphs. It was as if he were visiting the notion—sometimes exceedingly long paragraphs can impede one’s enjoyment of a story—for the first time. He was that kind of genius, whose understanding of the workings of his own fiction was, I think, largely separate from ideas of audience.

But he went with the changes. There’s room for debate whether or not they were best for the story.

We published “Mr. Squishy” with the fake name, but I don’t think we fooled anyone for very long. Dave had at least four distinct styles, maybe more, but “Mr. Squishy” was written in his most recognizable. (OK, acknowledging that this is ill-thought-out and incomplete, a stab at his four most clear-cut styles would be: (1) the plainspoken and fluid journalistic style demonstrated in his McCain piece (this is the style that goes down the easiest, and where his passion and opinions are most unguarded); (2) the ramped-up journalistic style of the cruise-ship piece and similar pieces of epic observation (these pieces have the more elaborate footnotes and digressions); (3) the humor-isolating and accessible style of Brief Interviews and the “Porousness of Certain Borders” stories; and (4) the dense, discursive, and insanely detailed style of his novels and certain stories.)

“Mr. Squishy” was probably closer to Infinite Jest in style than any other short story he wrote, so I wondered aloud to him whether anyone would really buy that it was written by someone named Elizabeth Klemm. And even if they did buy it, wouldn’t they accuse Ms. Klemm of aping DFW’s style? We both sort of laughed it off and agreed to let the whole thing play out.

About a day after shipping the issue, we started getting letters and e-mails, even phone calls to the office, demanding to know whether Wallace was the author of this incredibly Wallace-like story. And the jig was up shortly thereafter, because he went on a book tour, and everyone was asking him about it, and I think he felt bad about fibbing about the authorship issue. At the same time, a few of us McSweeney’s people were doing events, too, and people kept asking. It was killing us, fibbing about it to very nice (though very intense) DFW fans. We’d perfected a non-answer answer, which was something like “Well, it came through the mail, and the byline on it was Elizabeth Klemm.” Usually, the fans would walk away, feeling that, with this non-answer answer, their suspicions had been confirmed.

Not too long after, Dave owned up to the story, and we did, too. He was too honest to fib, too recognizable to hide, too singular to fool anyone.

Thank you all for continuing to share your thoughts and memories. Please keep them coming. This site will continue to celebrate his life for the foreseeable future.

— Dave Eggers

When I was a younger writer caught up in the fever dream of what would be my first abandoned novel, I wrote in a state of panic and dread to David Foster Wallace, then stationed at Illinois State University, in Normal, Illinois. Call this invasion an act of literary stalking, but this was before Infinite Jest came out and I’d read excerpts in various literary journals and was hooked. I don’t know if Dave received much fan mail or if he was one of those guys who, if written to, felt compelled to write back. Whatever, a letter arrived a few weeks later, postmarked from Peoria, Illinois. Inside was a neatly folded note, handwritten in bright-red ink, the penmanship slanted and a smiley face adjacent to his signature. This is what it said:

Thank you for your nice letter. I’m sorry that I have no words of wisdom or inspiration. I get sad and scared too. I think maybe it’s part of the natural price of wanting to do this kind of work. I wish you well.—Alec Michod

Three times I saw David Foster Wallace speak: once at the Hammer Museum at UCLA; a second time back at the Hammer in conversation with Mona Simpson; and at the Webb Schools in Claremont. The Claremont event was a workshop for private-school English teachers.

When I finally got up the nerve to ask DFW a question, I felt red-faced and nervous. I asked him how I, an ordinary, seldom-published writing teacher, could ever have any clout with my students, as opposed to a teacher like him, who could point over his shoulder at the genre-shattering masterpieces he’d written to get his aspiring writers to be like, “Wow, this guy’s not fucking around.”

He answered that as teachers what matters is that we provide a generosity of comment and time, that we display to our students a commitment to their work. And, sure, they’re still going to write a story about the boy with the backwards ball cap getting surly at the keg party, but maybe we can take them seriously and have them write a better, more lucid and honest, backwards-ball-cap-boy-at-kegger saga.

—Alex Ross

Needing something honest but nonfawning to say while he signed my book at the Strand in 2006, I told him that “The Suffering Channel” was the best thing I’d read about September 11.

“Really? Some people think it’s tasteless,” he said.

“No,” I said (and fawned), “nothing else gets how it really felt, how it made everything seem so silly, but nostalgic, too.”

I expected a contemplative “Thanks” (and I would’ve left happy), but he replied: “Well, I hope you’ll find a larger platform for your views.”

This still makes me laugh out loud.

—Rob Stillwell

In the year 2000, my friend and I rented a car and drove all the way from California to Bloomington, Illinois, where David Foster Wallace was teaching at the time. I wanted to finally meet him in person, after I had been publishing his books in Italian for a few years. He had told me on the phone I could meet him at the local secondhand bookstore. The store had a big mirror on the back wall, and when he entered (I was already there) I caught him looking at himself in the mirror, with a curious expression. Unlike in any picture I had ever seen of him, his hair was surprisingly short, and he was wearing no bandanna.

He addressed me with a funny Spanish “Señor Cassini?,” probably thinking the Spanish could easily pass for Italian. I told him I expected to meet a longhaired man, and he replied, “Yeah, I just had a haircut, and I can’t get used to the way I look now. When I entered the bookstore a minute ago, I couldn’t recognize myself in the mirror.”

He was wearing shorts, a T-shirt, and I noticed how he had apparently cut the upper part of his right sock, in order to carry his wallet in it. We then went to a restaurant for lunch (cheeseburger, french fries, Coke—he taught me what a “free refill” is: we have nothing like that in Italy; if we did, everyone would drink liters and liters of free soda) and had a nice, long, complicated conversation.

At one point, he confessed with obvious embarrassment that he and his girlfriend had recently gotten cable TV, which he had for a long time resisted getting, and he told me how every time he found something good to watch, he immediately feared that there might be something better to watch on the next channel, and therefore he would never stop zapping, and never really watch anything at all, which usually resulted in an argument with his girlfriend.

He insisted on buying my friend and me lunch. When I asked him to sign copies of his books I had been carrying with me during my road trip (a copy of Infinite Jest and Italian versions of his books I had published), he wrote, “To Marco, who actually made me pay for his lunch.” (In the meantime, the waiter had prepared his doggy bag; Dave had eaten only half of his cheeseburger and was happy to take the remaining half to his Labrador back home.)

Then we moved outside the restaurant, to the parking lot, because I’d asked him to show us on a map the road to wherever my friend and I were going next. When he opened his car door to get a road atlas, I saw his red bandanna in the back, and asked him if I could have it. He told me I could, but in exchange he wanted the T-shirt I was wearing, and that I had bought two months before in Rome, at a flea market, for 3,000 lire (a couple of bucks). It was a Lucky Charms T-shirt, and he said he used to eat Lucky Charms every day when he was a kid.

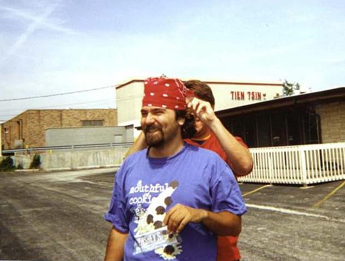

Exchanging pieces of clothing in a parking lot outside a restaurant in rural Illinois must have been quite strange, and therefore my friend decided to take a few pictures of this mise en scène.

In the four-frame sequence, you can see:

1. DFW, eyeglasses in hand, putting my red Lucky Charms T-shirt on over his Notre Dame Fighting Irish T-shirt, while I’m trying to cover my nudity with yet another two-buck flea-market T-shirt, this one celebrating Hershey’s Cookies ‘n’ Creme.

2. DFW explaining to me the sophisticated techniques of bandanna-wearing.

3. DFW putting his very own bandanna on my very own head.

4. The two of us proudly showing how happy we are with our new pieces of clothing.

Later on, all the other times we met (not many) or corresponded, directly or through his agent, Dave made sure I was informed about the status of my T-shirt. He said it was “the gym T-shirt,” the one he used as much as he could when he went to the gym.

One day, two years ago, his one time in Italy, we were in Capri. He was there for a literary festival, and when he saw me he said: “Hey, Marco, I’m sorry—I left your Lucky Charms T-shirt back home. That’s my favorite T-shirt.”

Then he started to explain to his wife what he meant by that. I mentioned to both of them that, years before, I had lent his bandanna to Zadie Smith for an afternoon. She was impressed by the fact that I owned David Foster Wallace’s bandanna, and even mentioned it in a foreword to a book (an anthology that was, incidentally, named after one of his pitch-perfect short stories).

Those were the subjects of our talks: my T-shirt, his bandanna. Not books. Not writers. Not fiction. Just silly clothing. Lucky Charms.

—Marco Cassini

I never met the man, but to Mr. David Wallace I owe my current situation in life. And he left a pretty funny voicemail. My wife and I have a mutual friend who several years ago realized that we were the only two people he knew who had completed Infinite Jest. On her side, she had implored him to find someone with whom she could discuss the book so she could ask the question she’d been dying to ask such a person, Was it worth it? On my side, we were driving to a ski trip, discussing books, and he mentioned Pynchon. Of course Wallace came up. He asked if I had read Infinite Jest; I said, Yes. He stared at me in the rearview mirror and said, I know someone who will sleep with you. Nine months later (these wheels turn slowly), he brought us together at a Halloween party. I walked in early and she was already there. Mike introduced us—Steve, Karen, Karen, Steve, Infinite Jest, go—and walked off. I talked about it for a minute or two, then said, Yeah, I liked it, but it probably wasn’t worth it. The rest is, as they say, history.

Except. There’s more: the voicemail. Karen and I fell in love, got engaged on the side of a mountain, and planned a shindig. At the reception, among all the toasts, a family friend stands up with a tape player. She recounts the tale. She turns on the player. David Foster Wallace is saying, Uh, um, this is really a strange and almost horrifying thing, but I hear that a couple, Steve and Karen, are joining themselves in holy matrimony because of my book? He goes on to give a funny, rambling, beautiful benediction that we’ll always treasure.

So, Mr. David Foster Wallace, thank you for the possibly-not-worth-it tome, dozens of incredible essays, a heartfelt voice from beyond, and a beautiful life with my wife and little boy.

—Steve Beeson

In the summer of 1995, I was the features editor of Tennis magazine. I was trying to get more good writing into its pages and proposed to the editor-in-chief that we assign a story to a writer named David Foster Wallace, who’d done a piece for Harper’s about playing junior tennis on the windy plains of Illinois. When I contacted him through his agent and proposed that he come to New York, spend Labor Day weekend at the U.S. Open (always the middle weekend of the tournament), and write about its “Americanness” in that context, he quickly agreed (for much less money than he could have demanded). As a junior tennis player, he’d pored over the magazine religiously and was excited to now be on assignment for it. Because I’d read his 1994 Harper’s story about the Illinois State Fair and knew he could spin out riffs funny enough to induce nasal-milk-siphoning, I pleaded with the editor to let him go at least 3,000 words.

I met him at the site in Flushing Meadows, secured him the media pass that allowed him to roam the grounds at will, and we settled into the stadium to watch Pete Sampras play a young Australian, Mark Philippoussis. David seemed shy but confident, and during the course of the match we talked a lot of tennis (he admitted that poet Stephen Dunn had kicked his ass in a match at Yaddo) and a little literature. He didn’t seem to take many notes.

Though the piece was not to appear for another year, three weeks after Labor Day I received a printout of the 7,000-word story and a letter explaining that he was likely to be “a truculent editee.” The story, as I had hoped, was not just about the Open but about New York City, athletic prowess, the American melting pot, capitalism, food, and a thousand other things. It was also hilarious and hyper-perceptive and poignant. The match featured “two Greeks neither of whom are in fact from Greece, a kind of postmodern Peloponnesian War.” Sampras’s “whole body can snap the way normally just a wrist can snap.” Or in a footnote about the food: “Take, e.g., a skinny little Häagen-Dazs bar—really skinny, a five-biter at most—which goes for a felonious $3.00, and as with most of the food-concessions here you feel gouged and outraged about the price right up until you bite in and discover it’s a seriously good Häagen-Dazs bar.”

Far from being windy at 7,000 words, it seemed positively concise for the amount of ground it covered. I eventually convinced the editor to let it run at length and spent many overtime hours in the office with the art director fiddling with Quark to get the footnotes right. When I sent him the galleys, Dave, typically kind and funny, thanked me for the “serious boater-and-cane footwork” he’d (rightly) assumed I’d had to do to get it past the editor in that form. In fact, as I’m sure his other editors will attest, he was a fierce defender of his words but far from “truculent”; his red-pen replies to my black-pen comments often included expressive-eyebrowed little eye-dot and line-mouth faces and even a “whoopsi” when I corrected a factual mistake. (The story didn’t appear in either of his nonfiction collections. Tennis has posted it on the magazine’s website: http://www.tennis.com/features/general/features.aspx?id=145230.)

In the year between when he wrote the story and when it appeared, Infinite Jest was released, his now-classic Harper’s story about a cruise appeared, and he became an uncomfortable literary celebrity. He thanked me for coming to his “Boschian” book party for IJ, adding, “I’ve never been to a Publication Party before, and if that one was representative I’ll never go to another.” One of the things I admired most about him, especially now that I’m writing rather than editing, was his devotion to writing as a moral and even religious act apart from the trappings of the literary life. But for all that, he never hurled pronouncements from a monkish aerie. He was able to be both more serious and more entertaining than any other writer of his time.

We continued to correspond occasionally over the years, usually after I’d spent a blissful couple of hours with his latest story and felt compelled to write to him yet another fawning fan letter. Inevitably, the card I received in return found some way to make me feel like I’d taught him something new (as if) or that the world was a better place with me in it. I wish I had that gift. Today the world is not a better place.

—Jay Jennings

I was a student of Dave’s at Illinois State as a freshman, before Infinite Jest had come out. He would often come to class after playing tennis, in cutoff jeans, wearing a bandanna. After pressing him later in the semester, he explained that “David Foster Wallace” was chosen by agents or publishers to differentiate him from other Dave or David Wallaces. We all called him Dave.

I once wrote an essay for him about a story we had read for class (I think it was The Big Nowhere by James Ellroy). We hadn’t quite figured it out in our class discussion, but, after some thought, I managed a decent theory in the essay. He told me later that I had nailed the story and wanted very badly to give me an A. He had to give me a B, though, citing 52 instances of comma misuse for the downgrade. He told me, somewhat pugnaciously, to learn how to use a comma.

Infinite Jest came out a couple of years later. For a whole semester, I lugged it with me on the train to Chicago, where I was then going to school. Next to the grammatical acrobatics, insane research, and heavy plotting, Dave had an honest humanity that made his stories worth reading. I had some friends, daunted by Infinite Jest’s size, who gave it a cursory glance and wrote him off as an author for literary hipsters only. Those who gave it more than that found the same things I remember from class: that Dave was never a snob, never dismissive, never exclusive, but only interested and kind.

—Matt Lentz

I always vaguely felt like he was the father of what I was up to—or not the father, exactly, more like the big brother. I remember in grad school there were many traditions of writing being discussed (Tobias Wolff, Gordon Lish, etc.), each with their own set of theories and concerns, and all of us grad students fell in line with one or another of them. And then suddenly here came DFW, hyper, voluble, one in a million, and we were all suddenly rushing behind, as if he were the big brother who rebels and then all the other siblings fall over themselves trying to rebel too, maybe not in exactly the same way but certainly influenced by his example.

And he was so irrepressibly cute and endearing. His funny clothes, his funny hair, his gargantuan books that you lugged around, the crazy stories you’d hear about him climbing around in the trees outside the house of a woman who had spurned him. He just seemed to me to be bursting with intelligence, enthusiasm, charm, and even humility. When he won the MacArthur, I remember thinking: “One for the team!” as if he were the leader of my brat pack—even though I’d only corresponded with him a few times and had never met him.

I listened again this week to his Bookworm interviews with Michael Silverblatt. My favorite, the one that seems to me to capture the quintessential DFW, is the one where he talks about the fantastic, genius book A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. Wallace accidentally hijacks the conversation and winds up holding forth on what he doesn’t like about his own book and Silverblatt is dumbstruck. You can hear it in his voice toward the end: Silverblatt isn’t even sure why they’re discussing what they’re discussing—and it’s absolutely the only time I’ve heard that in Silverblatt’s voice. Wallace has left him two steps behind, and now Wallace gallops further ahead, leaving whatever they were talking about in the dust, James Thurber or whatnot. Wallace is on to religious texts now, enlightenment, and how Wallace himself is so lacking, so absurdly lacking in comparison to the great works of the world! And in the final moments, while poor Silverblatt is trying to read the credits without laughing, Wallace announces, “I’m going to bang my head against the wall for 30 seconds now.” Silverblatt shouts “Stop!” and you, the listener, hear a thud.

He was a beautiful, fantastic, brilliant man, and we will all miss him terribly.

—Deb Olin Unferth

A year and a half ago, Dave flew out to New Mexico to give a reading, and I volunteered to pick him up at the airport. For company, a friend went with me, also a huge DFW fan, and we waited, rather nervously, with sweaty palms in our pockets, for Mr. Wallace’s flight to get in. Dave arrived in high spirits, dressed more like he was going on a camping trip than about to give a literature reading, and he was hungry. “We could just drive-thru at Burger King,” Dave said, “get a Whopper.”

Like hell I was going to take one of my favorite authors to Burger King when there was absolutely no rush and plenty of other good options.

“I know of a little sushi place,” I said.

Sushi sounded fantastic to Dave. He must have been ready to eat his shoes by this point, but was still impeccably polite.

Over lunch, the three of us talked about books, writing, theory, teaching, mutual friends, many things. He was such a humble, genuine person it was shocking. This was simply not how badass, famous writers were supposed to behave. Dave insisted on picking up the check despite our protests.

As we stepped out of the restaurant, he excused himself and walked toward the entrance of a nearby business, the opposite direction from where we had parked.

A moment later, my friend leaned to me and asked: “Why is David Foster Wallace digging through the trash?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

Dave had lifted the plastic top off a trash receptacle and was rooting around. I expected someone to come out of the business and tell him to leave, threatening to call the cops. After a bit, he put the lid back on the trash can and returned, a beat-up Styrofoam cup in his hand, one of the microwave-ramen-noodle varieties. The three of us walked back to the car in awkward silence, my friend and I wondering what just happened.

“Spit cup,” Dave said. “You mind if I dip in your car?”

“Be my guest,” I said. That’s how we found out Dave Wallace, the most unpretentious novelist we’d ever met, chewed tobacco.

His visit meant a lot to me. I’m very sad he’s gone.

—Blase Drexler

I met David Foster Wallace in 1998, when I was coordinating a literary/music series at the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, and he was there reading selections from A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. I met a lot of artists during that job, but he stood out, and I’ve found myself incredibly sad at the news. Here’s what I remember from our brief encounter:

- He was so gracious and polite. He was worried that his hotel incidentals were going to be mistakenly charged to the museum; I had to reassure him they weren’t. I liked this about him.

- He was painfully self-aware. I asked him to do a short interview for UCSD-TV, the local university cable station that always filmed our series. He didn’t want to do it, even though I told him that no one would see it. In the end, he did it, and I felt bad that I pressed him, because it was clear from watching the interview how totally uncomfortable he was.

- We both had pound dogs, and agreed that was the only way to go.

- He shared the bill that night with Sharon Olds, and was starstruck by her, which was cute. I think as many people were there to see him as to see her, but he treated her like royalty. The band that night was fairly loud—too loud for Sharon Olds—and he sweetly ushered her outside and waited with her until they were finished. He had no ego, and he was so talented.

It’s not often you get to meet someone like him, and I’m grateful that our paths crossed, even if it was brief. I will miss him.

—Jennifer de la Fuente

I had never tried to contact a writer or any sort of celebrity before, and haven’t since, so I don’t know how common it is to get a response, but he was kind enough to reply to a letter I wrote him in 2006, after I read “Good Old Neon” in Oblivion. The story was everything I had been trying to say in a master’s thesis, done so much more clearly and engagingly than I could ever have hoped for. I was horrified and ecstatic. I told him it now seemed to me that continuing with scholarly writing seemed not nearly as promising as trying to convey these ideas some other way—fiction writing being the likely suspect—and asked him, “What does it take to go from abstract ideas to specific stories that embody those ideas in a way that feeds a reader?”

He doodled stars and circles and lines on a lined notebook page and told me that “the standard CW class line” was that “if you start with abstract ideas, you end up using the characters + story as a kind of scaffold for the ‘message.’ Most of my own experience confirms this rather [”annoying" crossed out] simplistic dictum—at least, pieces that start mainly as ‘ideas’ rarely come alive, and usually end up as scrap (only 2 exceptions, both in early 90s …)." He expressed his doubt that any scholarly writing could convey the same themes as a short story, because “good fiction has value because it’s a way to talk about stuff that can’t be talked about any other way.” He stepped gently around my delusion that I had been writing something similar to what he had written and managed to end by encouraging me to soldier on: “If you can talk about them straightforwardly, do so—but I doubt they’ll end up being ‘the same.’” His closing was a smiley face.

Something I circled in pencil in “Good Old Neon” in 2006 comes back to me now: the number of times the narrator uses “firepower” as a metaphor for intelligence. He sees the mind as a weapon, and he expects people to turn these weapons upon each other. But the narrator’s mind has turned upon itself. The title hints that a whole life, including the life of the mind, is really just a flickering bit of light, not gunpowder and fire. Yet the narrator succumbs to the endless inner monologue that batters him.

I am sad now because his words, his mind, were such a companion to me and to others, yet clearly a terrible master. I wish that I could have returned the favors he has done for me in some small way.

And I am sad in that selfish way: because there will be no more words from him to expose me to myself, to show me others with more awareness than I have ever mustered. I will have to try to do that for myself, appreciating his insight as it stands. For that’s what the light and heat from his words did. It wasn’t a spectacle of fireworks for the reader to gape at. It wasn’t a barrage of weapons aimed at the reader. It was an illumination of how things are. For then we can take action. Only when we can see can we consider what to sustain and what to change. And he helped us see.

—Elizabeth Silas-Havas

A month or so after I first moved to New York, in 2003, I attended my first reading in the city. David Foster Wallace was appearing in support of his mathy treatise that even the white-knucklers among his fans—myself included—either wouldn’t read or couldn’t hope to understand. And so I headed to the Barnes & Noble in Union Square with the intention, impure and yet devotionally sound, of simply getting a load of my literary beacon and his golden gloves. I’d do my best to hang on to infinity and what-all, but a glimpse of kerchief would make a night of it for me. What I recall most was the upright, sincere, slightly abashed figure he cut while struggling to make himself clear, an aspect he could maintain even while gamely slaying a wobbly inquiry during the tedious Q&A. That and the fact that, when dispatching what are commonly described as “air quotes” (which he did often), DFW would raise a single, pink hand and with his forefingers hang not two but three consecutive lingering hooks by his ear. Dumb thing to remember, but there it is; the mind is a funny thing. I think, at the time, that third hook snagged me because it was both so deliberate and so natural: even his air quotes are singular; he can’t help it. The night, as predicted, was made.

—Michelle Orange

He helped me to stop wrecking my life, showed me how to help other people and why I should bother.

He succeeded in getting me to stop trying to sound like someone else when writing stories, particularly someone British from a long time ago.

He tried to get me to stop “giving my talent the finger” through half-assed grammar. He tried to get me to stay with it when things got hard.

He did teach me that cereal tastes better when stored in the fridge.

We all love and miss you, Dave.

Rest easy.

—A

I’d like to add on to Dave Eggers’s reminiscence about a dinner we had with Dave Wallace. I was editing fiction at Esquire, where Dave E. and I both worked, and we took Dave W. to a diner on Ninth Avenue. The idea of the Daves together at an expense-account restaurant in midtown made me want to throw a dark cloth over my eyes, so a diner it was. As we walked down the street and into the restaurant, Dave W. was polite to the point of paralysis—as excessively polite, I remember thinking then, as a cartoon chipmunk (“After you, sir”; “No, sir, I say, after you!”).

I remember that Dave W. was wearing a blue T-shirt with a long-sleeved white T-shirt underneath it, and a boxy sports coat, which he said he’d bought recently at the nicest department store in Bloomington. This was white-tie attire for Dave W. He was pretty tall, and squarish, and walked with his head slightly bent, as if he were trying to make himself smaller, trying to protect the self-presentation of a short person with whom he was speaking. He had acne, facial hair, and a sebum-rich complexion. He smelled like Old Spice deodorant.

Dave E. ordered some sort of chicken-nuggety thing. Dave W. ordered a turkey burger, and, firmly but politely—again, he really was excruciatingly polite—told the server: “Well done. Italicize ‘well done.’” He also ordered a hot Lipton tea. In restaurants, he used Lipton-brimming teacups as spittoons. Before I knew Dave W., I had never really noticed, or thought to notice, how similar tea and tobacco spit actually really are.

Unlike Dave E., however, I barely noticed the cup during dinner; Dave W. was a master of stealth expectoration. I don’t know how he did it, because you would never actually see him do the deed. Or at least I never saw it. I suppose he would spit the split second you looked away, while you were examining your manicure or whatever was on your plate. How did he get the timing exactly right?

Dave E. had just returned that day from a trip to Thailand, where he was reporting a piece for Esquire. Dave W. was fascinated by Dave E.‘s observations about the elephants there, and asked a lot of questions about them; mostly he was interested in how the animals were treated. Then he asked Dave E. how old he was. Dave W. clearly didn’t care for Dave E.’s answer, because he pinched my leg, hard, underneath the table. Dave W. said later, and frequently, that he felt he had reached a point in his life where everyone was suddenly younger than he was.

He was a huge drama queen.

Dave W. was finishing the manuscript of Brief Interviews With Hideous Men, and we talked about the title. Dave E. had believed (we don’t know why) that the title was Brief Interviews With Heinous Men. Dave W. gently corrected him. I helpfully suggested that maybe, just maybe, “heinous” actually would work better in the title. (“That’s why you get paid the no bucks,” as Dave W. said once, in another—but nevertheless applicable—editorial situation. A line I’ve stolen from him a million times.) The Daves disagreed with me, and the subject was dropped.

I was going on vacation in a few days, and Dave W. made a comment, in a my-aren’t-we-fancy sort of tone, that we, Dave E. and I, were “big travelers.” He loved mocking pretentiousness (as he perceived it) of all kinds. You knew he hated a guy if he called him a “smoothie.” At this point in time, he enjoyed pointing out that he’d been to France only once.

When the bill came, Dave W. went right for the check. (He had long fingers, and his hands sometimes shook imperceptibly.) In my restaurant experiences with him, he would try to pick up the bill, even if it was self-evident, as it was in this case, that one or more of us at the table had (modest) corporate expense accounts. And Dave W. was much more persistent than most people (that perfunctory little fake-reach for the check people do) are. I had to swat at his hand many times before he finally gave up. There aren’t many people in the world who can succeed at making something as uncomplicated as paying the bill so, well, complicated.

Dave W. and I went to a play that night, a one-man comedy of the sort that’s described in ads as “outrageous.” The performer danced and sang and told light anecdotes about his abusive childhood in Queens. The play wasn’t very good, but it did have at least one good joke in it. I looked over at Dave W. I watched him laugh, in profile (he had a mild underbite; was it from the tobacco?). When he laughed, he really laughed, and threw back his head, revealing the pristine arc of his excellent teeth. It was a beautiful moment, and I let it hang there.

After the play, we went to a deli and Dave bought a bag of Ritz Bits and a bottle of Caffeine Free Diet Coke for himself, and a can of grape soda for me. His wallet at the time was, he said, a hand-me-down from his sister—a nylon clutch, red, in my recollection, and also, in my recollection, Velcroed. Let me put it this way: it was a lady’s wallet. I made fun of him for using it. He, in turn, found something to make fun of me for. Then he showed me his picture on his driver’s license. I asked him if his hair had been wet when the photo was taken, and he said he didn’t know. He took a closer look at the picture, and admitted that he still couldn’t tell.

Dave pulled his address book—an ancient, tragic thing bound together with ridiculous strips of duct tape—out of his bag. He flipped through the book and showed me a sample entry. His handwriting, as many people here know … oh, my, what to say about his handwriting? First of all, he printed, as in he printed (could he even write in script? had he ever?), usually in lowercase, but sometimes in threatening (you knew you were in trouble for something) all-caps block letters. It was the hand of someone who wanted very much to be understood.

His writing was precise, and penguin-y, but there was something weirdly … generic about it—as if it were written by a shape-shifting alien species, one trying to reproduce human handwriting. At the same time, it also looked as if it could have been written by a grubby eighth-grade boy. Which he was. His letters were slanted severely to the right, and he seemed to be not so great at writing in a straight line.

We went out onto the street and talked about the play. We talked about how we couldn’t understand how actors could handle saying and doing the exact same thing every night, and he said that he still couldn’t figure out if actors were very smart or very stupid. He decided on the latter. He’d hated the play.

As we passed in front of the New York City Public Library, I asked him a dumb question (so dumb that the substance of it is irrelevant)—thoughtless, incautious, and, most importantly, prying.

Dave stopped. He tilted his head. He looked at me without speaking. His expression was neutral. He wasn’t mad. He wasn’t offended. It was just that he had no answer to give. This, I would come to understand, was a gesture that meant: Words are vain.

It meant: I’ve got nothing for you.

It’s a gesture that is, of course, represented in his work this way:

“….”

Dave could be elusive and evasive.

He could be the most maddening person on the planet.

He could also be pissy. He could also be annoying. He could be mean. He could be remote, and ruthless, and reckless. He was filled with towering rages. He said that he believed he was 85 percent sincere and 15 percent full of shit. He lied, but then he would admit that he had been lying, and would apologize for it, excessively. But he tried to tell the truth. He tried to find the truth. He tried to be good, and he was. He was good. He was better than all of us put together.

And he was—is—loved.

He is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved he is loved.

—Adrienne Miller

Many people talk about Dave’s profile/essay/treatise on Roger Federer, which I can easily say is the best thing we’ve ever published at Play (the New York Times sports magazine). And I was fortunate enough to be his editor.

When we asked David to write about Federer, I was convinced that his famous love of tennis would be the reason he’d pass on the opportunity. But Federer, at that moment, had achieved such a level of excellence that even DFW, who almost always said no to magazine stories, couldn’t turn us down. He told me he watched tape of some matches and the sheer artistry of Federer’s game blew his mind. What he witnessed, he said, was impossible. He had no choice but to get to the bottom of it.

A few days later, he was off to Wimbledon. As any editor who worked with Dave knows, he didn’t much like to travel—at the time, he had no credit card and no cell phone. (This being 2006.) He had no idea how to negotiate with public-relations people (or, as he called them, “sports bureaucrats”). Nevertheless, we prepaid for a hotel, arranged for a loaner phone (which he took to calling the “cell phone from hell”), and put him on a plane to London. He called me the first night—at 4:30 a.m.—to tell me that he couldn’t find the press contact, that he wasn’t sure how to arrange an interview, and that he was really out of his element there, amongst the sports-media hordes. He was also confused by the bus system and worried that without a credential they wouldn’t let him onboard. In almost any other case, I’d have been pissed. It was 4:30 a.m., I was at my girlfriend’s, and I was asleep. It was Saturday. With David, though, eccentricity was part of the package. He was kind, funny, self-effacing, and genuine. Being a Midwesterner, he was exceptionally polite. He insisted on calling me “Mr. Dean” until the end.

Dave never really did get the interview we hoped for—he and Roger spoke for 10 minutes in front of a minder; 10 minutes that were reduced, naturally, to a footnote—but the story he wrote blew my mind. Our edits were minimal. Though he was willing to compromise, and welcomed input, the fact of the matter was that his brain was so large that he knew more than we did; he didn’t really study a subject so much as absorb it. Dave didn’t leave things out because he’d forgotten them; he left them out because he’d thought so much about them and decided they were unnecessary (for instance, any sort of substantive summary of why Federer was so great at this time; for him, the answer was “Well, duh”). What struck me most about him as the writer of this story (and not as a writer in general, because so many things struck me in that context) was how much he cared about every single letter in an 11,000-word story. It was an attention to detail and a love of language I’d never seen before, and likely never will again. We argued whether the correct punctuation was “power-baseline tennis” (his version) or “power base-line tennis” (the copy desk’s) and had 15-minute discussions over simple punctuation changes—and you’re willing to walk this road when the person on the other line is on the editorial board of the Oxford English Dictionary. He would call to preface a new addition, explaining that he realized that certain sentences were fragments or that syntax had been monkeyed with to uncomplicate an idea and that I should know each of these cases was 100 percent intentional and that the copyeditors should thus not make changes just for the sake of textbook accuracy. He is the only writer ever to convince (or even try to convince) the famously stubborn Times copy desk that we should temporarily ignore the paper’s famous serial-comma rule—the paper doesn’t use them; this really drove David nuts. His argument was that “10 percent of the cases become howlers without it” and offered the following example: “The elephant fell on the Snodgrass twins, Rodney and Pete.” Remove the comma and only two people are crushed by the elephant, whereas the writer might have intended the total to be four. Why complicate comprehension for the sake of a rule? When I told him I thought we were stuck—the institution is bigger than the individual, even this individual—he said he was willing to take up the matter with the copy tsar himself and added, “Just say the author’s an eccentric prima donna.” Then he laughed.

I don’t remember these quotes because my memory is particularly excellent. I remember because when I sat down to write this I pulled a file out of my desk at home labeled “DFW.” It is the only time I’ve ever kept a writer’s original manuscript, plus the proofs on which I scribbled his notes and changes as he read them to me over the phone from California.

Among the other things in that folder are Post-its with quotes and printouts of a few of our e-mail exchanges. (E-mail at this point was very new to him.) In one, he explains in great detail why the researcher (described as “unusually cool, for a fact-checker”) should trust his recollection of a specific point in an Agassi-Federer match because to not do so would require “2 hours and 3 long forms at UPS overnight.” Another starts: “Bonus: a brilliant editorial/photo idea for Josh Dean” and goes on to suggest what I still don’t think was that brilliant of an idea—a photo of Federer cut in half so that the right side would then be “a computer’s rendering of an x-ray of Federer (or facsimile) in precisely the same posture and attitude of the embodied side.” He signed it with a smiley-face emoticon. He later e-mailed about a “verbal precedent” of this concept from a “little-known” Mark Leyner book written in 1989 and signed off with “Notice I’m not calling you at 4:30 a.m. about any of this.”

Though Dave wasn’t a sportswriter, when he deigned to give it a shot he elevated the form to a level the rest of us couldn’t ever expect to match. (You could also say this about his food writing or his film writing or his math writing, I think.) He didn’t just talk about great shots—he talked about the concept of a great shot, spinning physics, mysticism, and celebrity into a single sentence that probably had a (very funny) footnote. But the thing that always struck me was that he could sizzle your synapses with intelligence and insight and literary pyrotechnics, but you didn’t need to read his sentences twice. They were brilliant and also colloquial. How he pulled that off is a literary voodoo I might never understand. To say he will be missed is an understatement for the ages.

—Josh Dean

I knew him a long time ago. He was my teacher, at Amherst, in the fall of 1987. He had long hair and always came to class with a tennis racket and sometimes cookies. He had us take breaks so he could smoke. We loved him. I can pretty safely say that all of the women in the class (and possibly some of the men) had crushes on him. I bonded with someone, who later became a good friend, because she was the only person in the class with a bigger crush on him than me. He was goofy and charming and cute and unlike any other teacher I’d ever had. But that’s not why I remember the class so clearly. He was a wonderful teacher, even at 25, even just out of grad school. He was tough in workshop but not mean. He made me look at writers I’d already discovered on my own—like Lorrie Moore—in a new way, and he introduced me to writers I probably never would have discovered on my own, like Lee K. Abbott. He had us read a Stephen King story about a possessed laundry machine (“The Mangler”) in conjunction with a prize-winning short story told from the point of view of a dead body (“Poor Boy”) to illustrate the differences between literary and genre fiction. There were other tangible things. I used to confuse “further” and “farther,” and, apparently, I did it quite often. In one of my stories, I’d confused them yet again, and in the margins, he’d written, simply, “I hate you.” I’ve never confused them since. He once left me a note, postponing a meeting, excusing himself by saying, “I’m so hungry I’m going to fall over.” While I was irritated that he wasn’t there, I immediately adopted that sentence and have been saying it ever since.

—Sue Dickman

I too am bewildered. Not least by the fact that the wonderful DFW told me two and a half years ago to hold on, keep going, accept the ebb and flow and mystery of life and wait till things got better. In 2005, I heard DFW speak at Kenyon (my alma mater). He gave a speech that encouraged graduates to see the extraordinary and the miraculous in the onerous workaday world they were about to enter. He urged us, especially, to have compassion.

Six months after I heard him speak, I was at my parents’ house doing nothing. Not a willing, restful nothing, but a hopeless sort of nothing. I had tried and failed to get a permanent job in D.C., had returned to the Midwestern city where my family lived, had tried and failed to get a job there, had grown less and less inclined to live, had gone to Chicago, had prayed for a miracle in Millennium Park, and had come home feeling like a triple failure. In this spirit, I remembered that David Foster Wallace had spoken to my exact situation.

So I got his address off the Pomona website and wrote to him. I don’t remember what I said—I whined, I wondered, I worried. I might have asked for answers. I didn’t expect a response; I rarely write to people I admire; I just admire them from afar. But in this case I felt the need to reach out. This was in February.

In March I had moved into an apartment and started a temp job. Leaving the house felt like redemption, and I slowly began to build the sort of simple, happy life I wanted. Then I got a letter with a California “Very Hungry Caterpillar” stamp on it (I still have the envelope). Do you mind if I don’t tell you what it said? Its contents have become far more personal and hard-hitting and apropos in the last few days. I can tell you that it showed immense humility on the part of Mr. Wallace, a lot of kindness toward a girl he didn’t even know, and solid advice for the trouble he knew I’d encounter in life even though I admitted to him that I was well-off, I had many options, and I was overwhelmed with guilt for being a white middle-class college graduate and still so sad. It was some of the wisest advice I’ve ever received from anyone.

Now I’m in New York (I just got here) and I could use some wisdom, again. The recent news breaks my heart. I will admit freely that I don’t know what to do. I want to help someone, somewhere, the way he helped me, but I can’t even make it myself.

—Amy Bergen

I attended a DFW reading of A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again at A Clean Well-Lighted Place for Books, in San Francisco, in 1997. I waited in line for him to sign my lemon-yellow hardback copy, trying to think of something funny and/or profoundly weird to say to him once I got to the front of the line, hoping I would make him laugh, that he would ask me my name, ask me if I wanted to go grab a beer with him afterward. Infinite Jest had been my companion during a three-month cross-country road trip I had taken the year before, when I was at an age where all I wanted was for someone to explain the world to me, which, of course, is a ridiculous thing to want, and which I now know is impossible, even though I felt (and still feel, perversely) that if anyone could come close to furnishing me with answers, it was DFW. What I took from IJ was that there were no answers, no closure, no explanation. There was only the journey. And while that may sound trite, a bit of fast-food Zen, it was exactly what I needed when I was younger, and, in retrospect, the best answer one could give to the eternal question of why. But I wasn’t thinking about all of this while I was waiting for DFW to sign my book. Looking back, I guess I wasn’t thinking about much, because as I handed him my book, all I could think to ask him was if he got to decide what the covers of his books looked like. He said no. He said someone in marketing made that decision. He said no one got to decide what their books looked like. Except for Vollmann. This is what he said to me. Then he signed my book, handed it back to me, and grimaced.

—Chris Okum

I met David Foster Wallace once. It was when he was interviewing for the creative-writing position at Pomona. (Though, if we were going to be honest, there was really no interview—it was his position if he wanted it, simple as that.) Wallace gave an hour workshop on a few student pieces and while we were all supposed to contribute in an attempt to emulate a “real” creative-writing class, we mostly just sat in a narcotic state of awe. “David Foster Wallace. Was here. In our crappy second-floor classroom with this ridiculous round table and dated decor.” At the end of the hour, he told us that if we were going to remember one thing, just one thing, from his workshop, it would be that we (as a society of grammatically impaired citizens) always used the word “nauseous” wrong. When we said “nauseous” we really meant “nauseated.” And that was it. He thanked us and a few weeks later he was offered the full-time job at Pomona. I never had a chance to work with or learn from Wallace, as I graduated that spring and drifted off into postcollege malaise. However, Wallace’s 20-second lesson on the use of “nauseous” never made it far from my tongue. Ever since that day, I have made myself into some forsaken grammar vigilante of appropriate “nauseous” use and I really don’t know why I did. Maybe it was the fact that someone of Wallace’s cerebral immensity felt that spreading the “nauseous” gospel was worth the final comment of a job interview and thus the least a literary disciple like myself could do was to continue to infect others with grammatical purity. Or maybe in those moments when I tell my friends that their hangover is not, in fact, making them “nauseous,” I actually share some transient kinship with the most epic of authors.

—John E. Goodson

Among David Foster Wallace’s many fine qualities was a genuine kindness. I attended his reading in 2004 at the Free Library in Philadelphia when an unusual moment occurred with a man who seemed not to be familiar with Wallace and had perhaps wandered into the reading. This fellow spoke during the question-and-answer period, from his seat, I think. I can’t remember if someone was walking around with a microphone or if this man just called out loudly. He seemed bedraggled and he spoke in an uneducated manner. I have to admit that I assumed he was homeless and just looking for a cool place to spend a summer afternoon. But he wanted to tell Wallace that he liked the story the author had just read aloud. It was “Incarnations of Burned Children.” I won’t forget the power of that reading, either. I believe this guy was just trying to say that he liked it, but maybe there was some sort of question in what he said. It wasn’t clear to me, and it wasn’t clear to Wallace. And suddenly Wallace made everyone in the room disappear apart from himself and this man who was trying to communicate. I wish I could remember the content of the discussion, but I think it’s more important that it happened, that it was back-and-forth and that it was so earnest. It clearly became important to Wallace that he and the man had an interaction. I was uncomfortable. I suspect others were. It was weird; a possibly drunk, possibly homeless man interrupting our little meeting of “smart” people with one of our heroes. There was precious little time and he was wasting it. But to Wallace, here was a human being reaching out to another one, and he wasn’t going to let that effort go unrequited.

Along with all the other things that he has now deprived us of, there is one less kind person in the world.

—Ben Timberlake

I knew of David Foster Wallace well before I read any of his work, because he attended the same college I did, albeit several years before me, and I’ve since become an avid reader of his magazine pieces (his Harper’s article on English usage is a particular favorite). So he came to mind back in the spring when my wife and I were plotting the details of our wedding. We’d gotten stuck on readings for the ceremony. We weren’t big on poetry, nor were we fans of Bible verses, so we were trying to land on something that would feel unique but familiar. I got it in my head that we should write to a bunch of people—strangers, friends, distant acquaintances—and ask them to send back a postcard on which they would tell us what they would have wanted said at their own wedding. I sent this request to a few people, but it was pretty clear that the wife wasn’t too excited by the idea and it fizzled before the summer began. This is all to say, of course, that the only person to actually respond was David Foster Wallace. He sent back the postcard I’d sent him—Little Richard and Bill Haley were on the front, looking jazzed. On the back, he’d written, in all caps, “Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem,” and then, “Much Joy to You Both, DW ’85.” My wife teaches middle-school Latin, but wasn’t confident about her translation of the phrase, so I looked it up on Google. The phrase was adopted, in 1775, as a state motto of Massachusetts; it means “By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty.” I can’t say why he would have wanted that read at his wedding or why he suggested it for ours, but as with pretty much everything else he ever wrote, I’ll enjoy setting my mind to the puzzle.

—Josh Fischel

Dave Wallace was my professor before he became my literary hero, academic adviser, and favorite late-afternoon conversational partner. It has taken tremendous effort for me to prevent my particular experience of him from blending into the stream of eulogies I’ve digested in the past 72 hours, but for some reason it seems like the most important thing in the world right now.

In class, Dave squirmed at the idea of being addressed as “Professor,” and would rather we call him almost anything else (with the exception of "Wallace"—a name he could only imagine emblazoned on the back of a football jersey). Early on in the semester, he referred to himself once as “Uncle Dave,” and the moniker stuck with him. After all, what kind of “professor” would offer me chewing tobacco in the middle of a lecture on conjunctive adverbs? Or have a special I’m-nervous-and-don’t-know-what-I’m-doing dance? And so when he signed the page of comments at the end of our essays “Avuncularly, Dave” we knew that the sentiment was both funny and sincere and that part of it was love.

In more casual encounters, we’d often talk about books. We could chat about the mechanics of a particular book forever, but the real test of its worth was whether it could “knock his socks off.” So while I could continue to recount the details of why Dave mattered to me, the list seems unneeded. You knocked my socks off, DW, and now my feet are achingly cold.

—Ashley Newman