The Special

Populations Unit

Arab Soldiers in Israel’s Army

an essay by Chanan Tigay

The following piece originally appeared in McSweeney’s 38.

To get the whole issue, click here.

On March 6, 2008, a small infantry unit from the Israel Defense Forces’ Givati Brigade left camp with the rising sun to comb the Gaza border for arms smugglers, terrorists, and assorted other unwanted visitors. Israel shares 1,017 kilometers of borderland with its neighbors, and patrols much of it every day. On the average morning, these patrols turn up very little. But when this group of soldiers pulled into the still-cool sand outside their base’s gate, the first of two Jeeps in their convoy caromed over a remote-control bomb and burst into flames. The vehicle jumped, hit the ground, and rolled to a stop. Inside, the front seat was slick with blood. A young soldier lay slumped against the dashboard, dead.

Had he been a typical Israeli soldier, what happened next would have followed a predictable routine. Haaretz, Yediot Ahronot, and Ma’ariv, Israel’s three major dailies, would have run front-page stories detailing the attack and the ensuing military funeral, their reporting flanked by outsize color photographs of the dead man as he was in life, a hand still resting on his shoulder where his wife or girlfriend had been cropped out. Human-interest pieces would have followed— Yediot recounting how, during the shiva mourning period, the soldier’s grieving mother had brought out his soccer trophies, Ma’ariv relaying an eerie story about something prescient he’d said the last time he’d visited. Meanwhile, in Jerusalem, the prime minister would convene an emergency meeting of his cabinet to hash out a military response.

When this soldier died, though, things went differently.

Suliman abu Juda, one of several thousand ethnic Arabs who serve, almost unnoticed, in Israel’s military, was buried in a civilian ceremony in the unregistered Negev village he called home—a settlement not officially recognized by Israel. In the days following his death, only one newspaper printed his name. The foreign ministry’s website, which lists soldiers killed in action, posted a nameless bio of abu Juda, a twenty-eight-year-old father of seven. Next to the profile was an empty box where a photograph would normally go.

The muted response came at his parents’ request. It was an effort on their part to avoid retribution from other Arabs in Israel, and from Palestinians who might have opposed their young son’s decision to cast his lot with the Israeli army. Abu Juda had two wives; one hailed from the West Bank city of Hebron, an incubator of Palestinian violence. His parents worried that their in-laws’ standing, to say nothing of their physical safety, would be jeopardized if their son’s name got out. And so abu Juda’s death was allowed to pass almost unnoticed.

His faceless online obituary is an apt illustration of the Israeli Arab soldier’s predicament. These men—and they are almost entirely men—are despised by much of the Arab world as traitors, and feared in Israel as a potential fifth column. The average Israeli Arab simply lives in the Jewish state; Israel’s Arab soldiers are its collaborators. Some, like abu Juda, fall in love and marry women from the West Bank and Gaza, and then, quite literally, must raise their rifles against family members. They are at once Muslims and citizens of the Jewish state; the first line of defense and a “demographic threat.”

In the summer of 2010, I traveled throughout Israel—from the unrec-ognized Bedouin villages of the Negev desert to the charmless military bases along the Lebanese border to the elegant villas of the Galilee Druze—and spoke to dozens of Israeli Arabs who had served in the military. These are not men who enlist in hopes of securing desk jobs or scoring posts in towns with good surf. Many serve in combat units; this being the Middle East, these units see action, and sometimes their soldiers die. Since its founding in 1948, Israel has fought seven wars and two intifadas. More than five hundred Israeli Arab soldiers have been killed in those conflicts. In a country as small as Israel, that’s a huge number.

And yet if these men are willing to risk their lives for their country, the thinking goes, Israel must be doing something right. Despite the misgivings Israeli Arab soldiers encounter on every side, many observers point to their service as a critical indicator of Israel’s unique position in the region: a stable, multiethnic island thriving in a sea of dictatorships and turmoil. This proposition, I will learn, is tested at every turn.

* * *

Shortly after I arrived, I called Faisal abu Nadi, a former officer in the G’dud Siyur Midbari—the Israeli army’s Desert Scouts Brigade, more commonly referred to as the Bedouin Unit. Abu Nadi is now the chairman of the Forum for Released Bedouin Officers and Soldiers, a small group that looks after Bedouin men in their post-military lives. He once had office space of a sort—a little concrete-and-steel clubhouse he tells me was built a decade ago as a meeting spot for Bedouin soldiers and their families—but three months before I call him, bulldozers on the payroll of a local building council came and razed the structure, which was built, illegally, on state land. About half of the Negev’s Bedouin live in illegally built shantytowns that are “unrecognized” by Israel—which tends to mean that they lack electricity and running water, and also that they are subject to demolition.

With no office to receive me in, abu Nadi invites me to his home. When I arrive he leads me past his shig, a sitting room where Bedouin men entertain other Bedouin men, and through a courtyard where he keeps a small menagerie of little beasts, all of whom must be extremely warm in the afternoon blaze. I count seven or eight sheep, a white stallion, a dozen pigeons in a coop.

“What do you do with the sheep?” I ask.

“The sheep?” he says. “We eat them.”

“What about the pigeons?”

“We take out all the organs, all the innards,” he says. “Then we stuff them and eat them.”

“And the horse?” I ask.

“That’s just for the kids to have fun.”

Abu Nadi is a very handsome guy—clean-shaven, graying, buzz-cut hair. Short, probably around 5’6". He wears jeans and a polo shirt and doesn’t smile much. He has two wives, he tells me, and plans to take a third. Thus far, his first wife has given him six children; his second, two. She’s feeding one of them in the kitchen as we head into abu Nadi’s living room and recline on shiny red floor cushions. Above the doorway there’s a framed map of the world, over which hangs a rifle—a wedding gift, abu Nadi says, from a friend. Two Hebrew plaques recognizing his military service sit beside each other on a shelf above the window. One of them spells his name wrong: TO FASIL ABU WADI, it says. Wadi is the Arabic word—also used in Hebrew—for a dried-out desert gully.

There’s another rifle on this shelf, too, and a saber hanging off-kilter in its sheath along the opposite wall. “It’s not real,” abu Nadi says, when he catches me staring at it. “It’s just for decoration.” Then he says the same thing about one of the rifles, and then the other.

Many Bedouin live in pretty rough dwellings—corrugated-metal huts with dirt or concrete floors, fire pits outside for cooking, oil lamps for light—but abu Nadi’s house is a house. It’s got only one story, and it’s not fancy, but it’s comfortable.

“The state is liable at any moment to bring a bulldozer and destroy this,” abu Nadi says. “You see this?” He gestures theatrically around the room. “It’s illegal.”

Abu Nadi chain-smokes Time-brand cigarettes, and he lights one before speaking again. “If the state destroyed the clubhouse for Bedouin officers and soldiers—not a pool hall, or a club for the elderly, or for young people—a clubhouse for Bedouin officers and soldiers where bereaved families meet, where youth preparing to enlist meet, where released soldiers and officers spend time… If the state comes and specifically, specifically, destroys the clubhouse, what do they say? It’s an illegal building. A building that has been there for ten years. It’s not new, not renovated. It was there ten years. But it was an illegal building. There are thousands of illegal buildings. Thousands! Why, specifically, this clubhouse? What’s happening here?”

This, as abu Nadi knows, is a simple question with no simple answer. The Negev desert comprises more than half of Israel’s land mass; at the state’s founding, some seventy thousand Bedouin lived there, making up the vast majority of the area’s population. Traditionally nomadic, Israel’s Bedouin had by then settled largely into semi-nomadism (moving seasonally), or had ceased wandering altogether. Like the Palestinians, most of them either fled or were expelled during Israel’s first days. Between eleven thousand and eighteen thousand stayed behind, and they became citizens of the new Jewish state. Since then, their position has been perpetually in doubt.

Eager to develop the Bedouins’ historic pasturelands for Jewish settlement and military bases, the Israeli government—through the army—initially relocated its remaining Bedouin to a small corner of the Negev they called the siyyag, which means fence. There, the Bedouin lived under military rule until the late 1960s. Beginning in 1969, Israel established seven Bedouin cities inside the siyyag, looking to ameliorate the situation by concentrating the majority of its Bedouin population in these government-planned townships. This has not happened. Today, half of the Negev’s 180,000 Bedouin—the population has increased tenfold since independence—live in the townships, and half have spread out into (or never left) the unrecognized villages, most of which are also located in the siyyag.

“I think the cardinal sin was not taking their connection to the land seriously,” Clinton Bailey, one of Israel’s foremost experts on the Bedouin, tells me. “From their point of view, whatever they had, they had legally, in the context of Bedouin law—which in their world was the only law that mattered.”

At various points, Israel has offered the Bedouin both money and land in exchange for abandoning their illegal villages, but many communities have viewed the offers as insufficient, and turned them down. Some are wary of leaving behind their traditional work to settle in cities lacking the infrastructure necessary to provide them with new jobs. Others are simply reluctant to start paying taxes. Another obstacle originates with the Bedouin who left Israel in the 1940s, a good number of whom still claim ownership of lands that now fall within the borders of the government-planned townships. Deferring to age-old custom, many Bedouin have refused to move onto land to which another tribe holds claim—which means that large swaths of the Israeli-built townships are considered by their intended residents to be uninhabitable. The townships have other problems as well: unemployment is extremely high, crime is rampant, and educational opportunities are abysmal. Experts also say that even if all of the Negev Bedouin suddenly decided to move into the state’s preferred, circumscribed quarters, there simply wouldn’t be enough room for them.

And yet despite this, the day I meet abu Nadi, Israel completely razes the Bedouin village of El Arakib, leaving its three-hundred-odd residents homeless. Later that same month, forces from the Israel Land Administration (ILA), a government entity that manages 93 percent of the country’s public land, destroy three houses in another Negev village, this one home to the abu Sulb tribe—a venerable family that sends more of its young men to volunteer for service in Israel’s military than almost any other Bedouin tribe. Two of the three destroyed houses belong to Arab soldiers in the IDF.

Later, I ask a government source familiar with internal deliberations on the Bedouin situation what bothers Israel so much about these illegal settlements. “A state has been built, and for the state to be built it has to have planning: to plan a village, to plan a road, to plan electricity and water and sewage,” he tells me. “And the state absolutely cannot provide services to anyone who just goes and settles wherever he wants, even if he’s been there for ten or twenty years.”

The inability to pump water and light into every far-flung com-munity doesn’t quite explain why entire villages are being destroyed, and my source seems aware of this. “Let’s say you have authority to knock down five hundred houses,” he says. “So, make some sort of priority. Make sure not to destroy the houses of soldiers. That’s it. Simple.” He pauses. “But I’m not in the Israel Land Administration. I’m not in the Bedouin Authority.”

Israel is far from the only country that has faltered in its efforts to settle its Bedouin. In the 1950s, Syria tried to limit its own Bedouin’s movements without much success; Saudi Arabia had similar difficulties, though subsidies from the state have helped smooth those over. Egypt, whose relationship with its Bedouin population has long been testy, has over the years destroyed its fair share of Bedouin homes. It bears mentioning, too, that if Israel were not the democratic state it assuredly is—if, for example, it were almost any of the twenty-one Arab nations that surround it, where men and women have recently begun to lay down their lives in order to claim their right to speak out—Bedouin veterans like Faisal abu Nadi wouldn’t be able to so freely criticize their government. And abu Nadi recognizes all this. He says he wouldn’t want to live anywhere else. But anywhere else includes the seven townships Israel built to house Negev Bedouin like him.

* * *

I hear different versions of abu Nadi’s concerns from many of the Arabs I meet. After a dozen such conversations, it becomes clear to me that the subject I’m pursuing—the question of how Israeli Arab soldiers see themselves, and what their service means for them and for the country—is, like so many questions that hang over this region, really a question about land. In their book Invisible Citizens: Israeli Government Policy Toward the Negev Bedouin, Shlomo Swirski and Yael Hasson observe that “the Negev Bedouin constitute the largest social group in Israel of whom it may be said that they still do not stand on solid ground.” Bedouin veterans want many things: financial support, jobs, electricity. But at the heart of their demands—and their disappointments—is the desire for a stable place to live, and the sense of belonging that comes with it. “If you solve the land problem, you solve everything,” says Elhaam Kamalaat, a Bedouin social worker and longtime army wife. “The rest is just social issues.”

For many of the men I talk to, military service was meant to be a solution of sorts. “It’s an entry ticket for citizenship,” says Col. Ramiz Ahmed, who as head of the IDF’s Special Populations Unit is charged with recruiting minorities and assisting them with issues relating to their military service. The army has long represented the most concrete way for Israeli citizens to demonstrate their dedication to the Zionist project; it offers both a stamp of approval and a networking crucible. Until very recently, joining the armed forces was considered an essential step in life among Israel’s Jews—up there with birth and death—and opting out, even for legitimate reasons, carried a lifelong stigma. Although most Bedouin do not enlist (they are not required to), those who do hope their service will open doors. It is as such that the army often proves to be a bitter disappointment.

“Those Bedouin who served are angrier at the state than those who didn’t serve at all,” says Kher Albaz, director of social services in Segev-Shalom, one of the government-planned Bedouin cities. “Every normal person—not just the Bedouin—who enlists to serve a state has expectations. Even the most nationalistic and Zionistic Jew who stays in the army beyond the time that’s required has expectations—personal expectations, financial expectations, quality of life, land. Otherwise he’s crazy, he needs therapy. That’s the name of the game here. And in the case of the Bedouin, it didn’t work.”

* * *

It can be difficult, at times, to tell how true this is—whether things really are not working at all, and will never work, or whether the sit-uation is less clear-cut. A month after I meet him, abu Nadi’s story still isn’t sitting right. Even given what seems to be a growing penchant for smashing Bedouin buildings, the decision to destroy a clubhouse for soldiers who had served the state honorably strikes me as so senseless as to defy logic.

“It wasn’t a clubhouse—it was a shig,” a high-ranking Israeli military official tells me one Saturday morning. He’s just returned home from services at a nearby synagogue and we’re at his dining-room table, sipping tap water. At the mention of the clubhouse, he smiles.

“Whose shig?” I ask him. “Abu Nadi’s?”

“Yes. His family’s.”

“And he just claimed it was a clubhouse? To get sympathy?”

He shrugs. “I know Faisal and I like him,” he says. “But it was a shig.”

* * *

Israel is a tiny country: about the size of New Jersey, with a smaller population. Of its 7.5 million citizens, about 1.5 million are Arabs; of those, several thousand are in active service in the Israel Defense Forces. Currently, about a thousand Bedouin serve, most in the standing army—and half of them, like abu Nadi did in his time, serve as trackers, putting their native mastery of the area’s deserts to work.

In accordance with Israel’s enlistment law, decisions about who is drafted are left to the defense minister. The Bedouin are not required to enlist, and never have been, and so must volunteer if they wish to serve. Some tribes have done so all the way back to the pre-state period, when the El Heibs joined the Palmach, the underground Jewish army’s elite strike force, to form a unit known as Pal-Heib. Since then, their tracking skills have become the stuff of legend—it would be unusual for an Israeli combat force to cross into enemy territory without a Bedouin tracker at its head. If they weren’t Arabs, one intelligence source tells me, the Bedouin trackers would be considered the most elite unit in the military.

(On the other hand: at one point I ask an Arab soldier if a Bedouin will ever command the Bedouin Unit. “Never,” he tells me. “The unit would fall apart.”)

At any given time, some two hundred Israeli-Palestinians also serve in the army—young men whose forebears did not leave Israel at the state’s founding. Depending on whom you’re talking to, and what their politics happen to be, these individuals may be called Israeli Arabs, Arab Israelis, Palestinian Israelis, Israeli Palestinians, or simply Palestinians. A handful of Circassians—Muslims who migrated to Palestine from the northern Caucasus in the late nineteenth century—serve as well. Unlike the Bedouin, they are required to do three years of military service.

The Druze, Arabs whose faith began as an offshoot of Shia Islam, are by far the most numerous among the IDF’s Arab conscripts. Ever since a 1956 “blood covenant” between Israel and Druze religious leaders, Druze men, like Israeli Jews, are subject to compulsory military service. This requirement excludes those Druze who live in the Golan Heights and never took Israeli citizenship after Israel captured the area from Syria in 1967; the Golan will be the centerpiece of any peace agreement with Syria, which for years has demanded its return as a precondition to negotiations. If the territory reverts to its former owner, Druze who served in the Jewish army would not last very long.

Initially, Israel’s Druze served only in a special platoon for minorities and in Herev, the so-called Druze Unit. In recent years, however, the entire military hierarchy has been opened to them, and Druze have begun to serve even in the most elite units. The highest-ranking non-Jewish officer in the history of the Israel Defense Forces is Maj. Gen. Yusef Mishlab, a Druze, who served as coordinator of government activities in the Palestinian territories and headed the Home Front Command when the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003. As Israel prepared bomb shelters and distributed gas masks in advance of a possible Iraqi attack (Saddam had launched Scud missiles at Israeli cities during the first Gulf War), the man overseeing the effort was Arab. The Druze may represent the most hopeful sign of genuine army-enabled Israeli Arab integration.

All these distinctions, though, make little difference to the type of person who would lay a mine in an IDF soldier’s path, or blow up a bus in Netanya, or fire a missile into Israel in the name of God.

* * *

At over six feet tall, Alaa al-Din A’Naim towered over the other members of his unit. He was so strong that his commanders in the Desert Scouts Brigade assigned the nineteen-year-old trainee the shoulder-bowing task of carrying a MAG, a thirty-pound machine gun other armies mount on Jeeps. On November 14, 1995, during a routine training exercise near the Gaza Strip, a member of A’Naim’s team stumbled over an undetonated grenade, left behind by an M203 grenade launcher. Of nine soldiers taking part in the exercise, only A’Naim died—although he held on for eight days before his broken body gave out.

“I came home from work that day at five or six,” says Salim A’Naim, Alaa’s father. I am visiting him at his home, in a small, unrecognized Bedouin village overlooking the ancient city of Nazareth. The Muslim holy month of Ramadan has recently begun, and A’Naim hasn’t eaten all day. As his wife and daughters lay down dishes for the evening’s meal, we take seats on the porch outside.

A’Naim, who bears a striking resemblance to the actor Anthony Quinn, speaks slowly and emphatically about Alaa, whom he refers to repeatedly as “the soldier.” His other sons are soldiers, too—Yusef, who joins us on the veranda, was nearly killed in Gaza during the now-famous raid in which Hamas gunmen kidnapped Israeli tank-gunner Gilad Shalit. A sweet, skinny guy with his head shaved bald, Yusef was guarding Shalit’s tank when it was attacked; since then, he’s carried a quarter-pound of shrapnel inside his torso. He flips open his mobile phone now, and shows me a picture of himself from before the raid. In it, a thick, muscular version of the shadow sitting in front of me proudly flexes his biceps. “I used to work out,” he says.

Shortly after grenade fragments perforated Yusef’s brother’s body, Alaa was airlifted to a Beersheba hospital for emergency surgery. His parents made the two-hundred-kilometer drive there in a taxi. “Every twenty or thirty kilometers they’d call us from the hospital,” A’Naim says. “‘Where are you? Where are you?’ Every twenty or thirty kilometers, ‘Where are you?’” When they arrived at last, medics were wheeling Alaa out of the operating room. “We ended up right next to him in the hall—him on the bed and us walking, together,” A’Naim says. Alaa’s big body, which his father had once thought indestructible, hardly fit on the gurney. “I kissed him, kissed his feet,” A’Naim says. “He was unconscious for eight days after that.”

He says “eight days” very slowly, as though the phrase were a ghost he’s urging forth from his lungs. Then he pauses, looks to the speckled tiles of his porch, and shakes his head. “On the eighth day the doctor called us into the room. I still remember what he said to us. He said, ‘I am the chief doctor. Even with American soldiers in their war in Vietnam, of three million, four million soldiers, maybe two or three had injuries like the one Alaa has.’ That was the day he died, and it was like an earthquake. An earthquake. A cab came and took us home. It was a black day here in the North.”

A’Naim pauses again just as the muezzin’s call to prayer rings out from a nearby mosque. It’s a perfect segue into the next part of the story. The sad part.

Immediately after Alaa died, his body was brought home and deposited in the mosque from which his father and I have just heard the adhan chanted. The A’Naim family gathered together and made their way there, to see the local imam recite the traditional burial rites before they took the shroud-covered corpse to its final resting place in the Muslim cemetery atop a nearby hill.

“We were outside the mosque—people from the army, the police, civilians, everything, waiting to be called in,” A’Naim says. Ten minutes passed, then twenty, then thirty. The mourners, huddling outside in the chilly November rain, grew anxious. A murmur passed through the crowd: What happened, what happened, what happened?

A number of relatives headed into the mosque to check on the delay. When they emerged, grim faced, several minutes later, the men headed straight to A’Naim.

“The imam refused to pray over Alaa,” he tells me. “The Islamic Movement opposed praying for the soldier because he served in the army.”

The Islamic Movement is a hard-line anti-Zionist group with connections to the Muslim Brotherhood. Its northern branch, which operates mosques near the A’Naims, is significantly more extreme than its southern counterpart. I ask A’Naim what went through his mind when he heard of their involvement, and he smacks the air by his ear. “First of all, a person like that, I don’t want his prayer,” he says, referring to the imam. “What hurts me—excuse the phrase—is that his entire clan isn’t worth my son’s shoe. That hurts me. It hurts. But I had no strength at the time. If I’d gathered my strength, I don’t know what would have been. It would have been another tragedy. It was a tragedy when he refused to pray, and he might not have stayed alive.”

Instead, the mourners located a Bedouin imam who agreed to officiate. They then made the short trip to the cemetery—only to find that they would, again, be refused entry because the dead man had been an IDF soldier. But this time members of Alaa’s unit who had traveled in to bury him would have none of it—they opened the cemetery by force, pushed aside its proprietors, hoisted the body onto their shoulders, and buried Alaa in a grave overlooking Nazareth’s Old City.

As the ceremony ended, Alaa’s commander stuck a plaque for fallen soldiers into the raised earth above the grave. When A’Naim returned the following morning to pay his respects, the marker had been dug up and smashed.

* * *

A few days after our first meeting, A’Naim invites me out to the Nazareth cemetery. We park, leave the car, and wind our way silently through dozens of tightly spaced gravestones, up one hill and down another, until we reach the fence at the far end of the grounds. A’Naim stops and gestures to the dirt before us, where a series of half-buried concrete cinder blocks trace the approximate shape of a shrouded corpse in the dry earth. Most of the graves in this section are bordered by flowers; all have headstones. Alaa’s grave is unmarked but for the encroaching piles of browning pine needles, thick like hair on a barber’s floor. Sighing, A’Naim gets to work.

He brushes off the cinder blocks around the grave, silently collecting handfuls of pine needles and dirt and filthy stones. He finds a hose and waters two tiny shrubs that have sprouted where the military plaque once stood. Then he stands, shuts off the hose, and, palms upturned to God, says a silent prayer.

On the way home he tells me that the imam who refused to pray for his son hasn’t been seen in the area since the day after the funeral, fifteen years ago. “He disappeared,” he says. “Left town. There are members of our clan who want to kill him. They’re still looking.”

A’Naim does not expect the Israeli government, or the army, to help him overcome the prejudices of his neighbors. His demand is different. Shortly after Alaa died, the army installed electric cables and water pipes in A’Naim’s village, bringing the bereaved family plumbing, light, and a new sense of normalcy. Now he wants to move his son to a resting place closer to home. His village, like abu Nadi’s, is “unrecognized”; there is no cemetery.

“Our dead are scattered in three different villages,” A’Naim tells me. “And we’re constantly asking: first of all, recognize us. After that, it’s very easy to establish a cemetery, right?”

It would be easier still to put up another marker on his son’s grave, or to move the body to a burial site closer to the rest of his tribe’s dead. That A’Naim has chosen not to is itself a highly political act.

“That’s not a grave,” A’Naim told me as we passed through Nazareth, on our way back from the cemetery. “It’s an embarrassment—for the state and for the army.” Not an embarrassment for forward-thinking Muslims like the A’Naims, who recognize the benefits of living in a modern democracy; not an embarrassment for the Islamic Movement’s leaders, who preach Israel’s destruction even as they enjoy those benefits. An embarrassment for the army and for the state, which can’t or won’t recognize the village where Alaa A’Naim once lived.

When I return home, I call Dan Shafrir, A’Naim’s lawyer, to get a sense of why a man who has paid an awful price for his children’s service to the nation has had such a difficult time gaining recognition for his village. Shafrir tells me that in the 1950s, the state evacuated A’Naim’s tribe from the area around Givat Ha’Moreh, in northern Israel, to make way for Jewish housing near the city of Afula. While the move to their current village was made with the full knowledge of Israel’s Interior Ministry, he says, there was never any official documentation. Today, Shafrir has thousands of pages of documents relating to A’Naim’s land claims, including letters from government offices acknowledging the need to help.

“If you read carefully, the letters say that Israel has the moral obligation to help Mr. A’Naim,” he says. “The problem is to turn the moral obligation into a real obligation.” Shafrir believes that A’Naim has a good chance to do just that; the process is stalled, he says, because A’Naim, whether out of a more pessimistic view of the legal system or a belief that the system should come to him—or perhaps, Shafrir says, due to nothing more than bad advice from previous lawyers—has yet to file his case.

* * *

Technically, Israel has been in a state of emergency since its founding in 1948. On May 14 of that year, about two hours after David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, declared the establishment of the state, Egypt (and, a short while later, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) invaded the newborn country and instigated a conflict that Israelis call the War of Independence and many Arabs refer to as the Nakba, the Catastrophe. Today, the Knesset votes each year to extend the emergency footing. This, coupled with a general sense among many people here that Israel, surrounded on all sides by Arab nations, is in a constant state of existential peril (a suspicion that has only been exacerbated since the ouster of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak and the ensuing unrest elsewhere in the Arab world), makes the presence of a large minority of Arabs threatening. This perceived threat has itself grown more acute with the Islamic Movement’s rise. Traditionally lackluster in its religiosity, much of Israel’s Bedouin population has, over the last several decades, fallen under the sway of homegrown Islamists. At the same time, the old-style “sheikh culture,” in which village headmen sat atop the Bedouin tribal hierarchy, has begun to decline, and the Islamic Movement has moved to fill the leadership vacuum. A significant increase in Bedouin crime—which increasingly spills out of Arab areas—has not helped the Negev Bedouin’s case among the greater Israeli population either.

(About 80,000 Bedouin also live in the verdant Galilee region; most of that number not only live in legal settlements, but are said to be about thirty years more socioeconomically advanced than the tribesmen of the Negev, who still endure drought and other desert deprivations. An additional 30,000 Bedouin live in central Israel.)

Shmuel Rifman, mayor of the Ramat Negev Regional Council, an umbrella organization of collective farms, kibbutzim, and community villages in the Negev, tells me that as the Bedouin have dispersed through the siyyag, they have not only hemmed in the neighboring city of Beersheba, precluding expansion of the Negev’s capital, but also wreaked havoc. “They steal sheep, transformers, army equipment, copper,” he says. “There’s nothing they don’t steal. Anything that will move, they steal. A night doesn’t pass when it doesn’t happen. It’s part of the Bedouin culture.” A state that wants to maintain sovereignty, Rifman argues, cannot allow its citizens to go wherever they please. “In today’s system,” he says, “the Bedouin wake up in the morning and they’re sitting here, then later they’ll put another tent on a hill over there, and gradually they’ll occupy the area.”

Rifman insists that the solution is not to recognize more Bedouin villages, but to encourage a mass migration of Jews to the Negev to ensure that, despite the Bedouin’s astronomical birthrate, Jews will continue to outnumber them for years. It’s certainly one way to approach the problem. But Moshe Arens, who served stints as defense and foreign minister in a series of right-wing governments, says the solution lies elsewhere.

“Instead of looking at the Bedouin as Israeli citizens who should be approached and coached into being loyal to the State of Israel and serving in the IDF, there are people who look upon them as some kind of enemy population,” Arens tells me over coffee and Danish. “It’s a very bad situation.” Widely credited as having opened the military up to more widespread Arab service during his tenure as defense minister, Arens says the army may just be the answer. “The IDF is the big equalizer. It’s been the melting pot for the Jewish population as well. It’s been the melting pot for the Druze population. It could be the melting pot for the Bedouin.”

For now, the vast majority of Israeli Arabs do not enlist, unwilling to serve a state they see as inherently inequitable. It’s hard not to think of what Kher Albaz has told me already—that the military melting pot, and its promise of greater integration and opportunity for the Bedouin, has yet to actually work. Part of the problem, too, is that many of those Bedouin who do enlist are the least educated among their tribesmen—unable to find decent-paying work elsewhere, they settle on the army. But because they lack basic skills, they don’t advance through the ranks.

When I talk to enlisted Bedouin, though, educated and not, they say that ultimately, despite the doubleness they feel; despite the dueling loyalties, the contradictions and the pain; despite the fact that, to outsiders, the Israeli armed forces seems the most unlikely of organizations in which to find a group of motivated Arabs—despite all this, they say, the army is the only place in all of the Jewish state where, for three or four or five years, Arabs truly feel Israeli.

“It’s the only place you find real equality,” says Adam Jorno, an Israeli Palestinian who served as a combat soldier in the 1990s. “I think that we, the Arabs of Israel, need to take a position. You’re either here or there. You have to be an integral part of the country, and that includes military service. There are those who say, ‘Oh, I don’t want to kill my brothers!’ So don’t be a combat soldier. Don’t go shoot Arabs. Go do another kind of service. You don’t have to be a fighter, but contribute to the country. Or take yourself and live with Hezbollah in Lebanon and fight against Israel.”

Jorno’s name wasn’t always Jorno. Once, his name was Khleikhel. But several years ago, when he was commanding a checkpoint along the border between Israel and Gaza, overseeing the entry of several thousand Palestinian laborers into Israel each day, a woman approached him and asked for a favor. He didn’t know her, but he quickly realized that she was a member of his very large extended family. She was building a house, she told him, and wanted to expedite construction. Could he arrange the permits that would allow two Palestinian workers to sleep over in Israel?

“It’s a small country, and our family is big,” says Jorno. He’s a successful lawyer now in Rosh Pina, not too far from Safed, representing Arab soldiers in the military courts. “They must have heard that there was an officer named Khleikhel at the crossing and said, ‘Let’s go get him to use his pull for us.’ It was a red flag for me. If I help someone like that, who knows what might happen? I don’t want to let someone sleep here, and then there’s an attack and I’m to blame.”

So he changed his name to Jorno. After that, he says, his relatives couldn’t make the connection. “That’s it,” he says. “I disappeared.”

* * *

Jorno’s concerns about being linked to terrorists are not unique. Reports surface from time to time about non-Arab soldiers receiving unofficial instructions to withhold vital intelligence from Bedouin trackers, for fear that they are colluding with terrorists or smugglers operating in the border regions. These fears, painful as they may be to men like Jorno, cannot simply be dismissed as ignorance or racism.

In July, I travel to northern Israel to meet Hassan El Heib. El Heib is the mayor of Zarzir, a Bedouin municipality located ten kilometers from Nazareth, and a lieutenant colonel (reserve) in the IDF. A gruff man with a distinct military bearing, he hails from the first Bedouin tribe to ally with the Jewish yishuv in pre-state days. He uses the majority of the time we’re together to hammer home the Bedouin’s long-standing military service, and to stress the common fate linking Israel’s Jews and Arabs. “We aren’t smugglers and drug dealers,” he says. “If Israel’s economy is good, it’s good for all of us. A terrorist that comes here and carries out an attack, kills all of us. We have to guard the house.”

What El Heib doesn’t initially mention is that his own brother is one of the exceptions to this claim. While serving in Lebanon in 1996, Lt. Col. Omar El Heib was gravely wounded by a roadside bomb planted by Hezbollah guerillas. Omar lost an eye in the attack, and was left partially paralyzed as well, with shrapnel lodged in his head. Despite his injuries, he continued to serve. Several years later, though, Omar was accused of passing military secrets to Hezbollah in exchange for money and narcotics. In 2002, a Tel Aviv court found him guilty, agreeing with the prosecutor’s contention that he had handed over maps, troop-deployment details, and the locations of high-ranking commanders. He was sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

When I raise the issue, Hassan El Heib doesn’t deny that his brother did what he was accused of doing—but he does his best to distance himself, and the larger Bedouin community, from claims that Omar’s motives were terroristic or nationalistic. “After he was injured, his mental capacity was like an eight-year-old’s,” he says. “How many Jews with a clear mind have spied against the State of Israel? If my brother did these things, it wasn’t ideological. He was caught up with a group of criminals, that’s all.”

After he was caught, Omar El Heib was stripped of his military rank and dishonorably discharged. If Hassan El Heib’s claim about his brother’s mental deficiencies is true, it is unclear what he was still doing in the army at the time of his arrest.

* * *

In 1969, the same year the first of the Bedouin cities was constructed, the state established legal machinery allowing Bedouin to submit claims relating to their relocations to a land settlement officer at the Ministry of Justice. By the early 1970s, some three thousand such claims had been filed, impacting nearly one hundred thousand dunams (25,000 acres). And so, in 1975, the government moved to formulate an official response to the Bedouin “land problem” in southern Israel, adopting the recommendation of the Albeck Committee, which a year earlier had determined that the entire Negev—including the siyyag —constituted state land on which Bedouin were “unable to acquire any rights, not even by virtue of protracted possession and cultivation.” Cognizant that humanitarian considerations would likely preclude high-court backing for mass eviction of the Bedouin from the siyyag —the very territory to which they had been forcibly moved by the Israeli military nearly three decades earlier—the committee proposed compensating Bedouin who relinquished their lands and moved to approved Bedouin settlements. The Albeck Committee recommendations have remained the basis for numerous government proposals, panels, and committees that have since sought to solve the land problem, all of which have championed policies that can be boiled down to three attributes: they deny Bedouin ownership of Negev lands; they support compensating the Bedouin for appropriated land; and they have not worked. According to Invisible Citizens authors Swirski and Hasson, forty years after those first three thousand land claims were filed, most are still pending.

Druze soldiers in the Israel Defense Forces, 1949. Courtesy of IDF Archives.

Defense Minister Moshe Dayan eulogizing Lotfi Nasser El Deen, killed on what was to have been his last day in the army, in 1969. Courtesy of Amal Nasser El Deen.

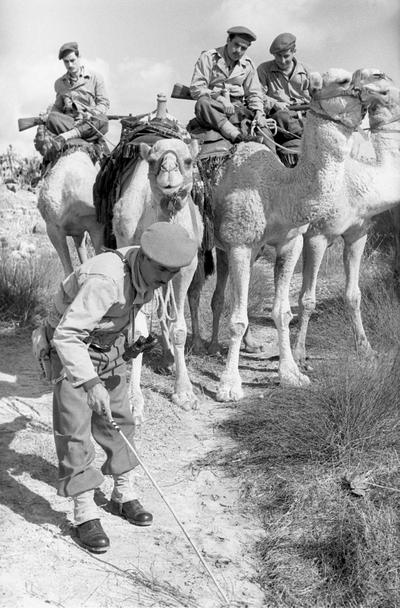

A Bedouin tracker inspects a mark in the sand, 1953.

Courtesy of IDF Archives/BaMachnaeh.

Circassian soldiers training in the Jezreel Valley, 1949. Courtesy of IDF Archives.

Soldiers in the Minorities Unit at a parade marking Israel’s

first Independence Day, 1949. Courtesy of IDF Archives.

A banner in the village of Daliyat al-Karmel, offering a reward for

information leading to the discovery of a missing Druze soldier. All

further photos, unless otherwise noted, by Chanan Tigay.

Faisal abu Nadi walking through the rubble of what

he says was a clubhouse for Bedouin soldiers.

The village of El Arakib, shortly after it was first demolished.

The remains of a demolished home in El Arakib.

El Arakib’s residents rebuilding, hours after their village was razed.

Breaking the Ramadan fast with the A’Naim family,

in their unrecognized village near Nazareth.

Faisal abu Nadi’s village, as seen from the roof of his home.

The unrecognized Bedouin village of Wadi Naam.

Arab trackers at Biranit, a military base perched on the border

with Lebanon. Several were fasting for Ramadan.

The Memorial for Fallen Druze Soldiers, with a tank

donated by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

Salim A’Naim says a prayer at his son’s grave in Nazareth.

The Memorial for Fallen Bedouin Soldiers in northern Israel.

Rafik Halabi at his desk in Daliyat al-Karmel.

Majdi Mazareib, chief tracker in Israel’s Northern Command.

Amal Nasser El Deen in his office at the Memorial for Fallen Druze Soldiers.

Hassan El Heib, mayor of Zarzir.

A Druze village in northern Israel, as seen from

the Memorial for Fallen Druze Soldiers.

Yusef A’Naim, before his injury. Courtesy of Yusef A’Naim.

Former defense and foreign minister Moshe Arens (in sunglasses).

Behind him is Hassan El Heib. Courtesy of Hassan El Heib.

In 2007, the government inaugurated the latest committee—an eight-member group headed by former high-court judge Eliezer Goldberg. The Goldberg Committee was charged with laying out a formula for compensating the Bedouin for expropriated land and locating substitute plots for those who were to be evacuated; after a year of study, the committee released its report. While agreeing with earlier decisions denying Bedouin land ownership, it nevertheless found that the Bedouin maintain “a certain degree of rights” to lands on which they have lived for years. The committee called on the government to recognize forty-six illegal Bedouin villages.

It seemed like a promising sign. In the lead-up to the report’s release, many Bedouin were cautiously optimistic that, at long last, their situation would be settled. And the Committee’s findings suggested that steps might indeed be taken in that direction. But no sooner had the Goldberg Committee issued its recommendations than Prime Minister Ehud Olmert rejected them, appointing a second committee to examine the Goldberg Committee’s work and see where it might be altered.

* * *

Israel’s national postal service doesn’t deliver to Umm El-Hiran, the unrecognized Bedouin village where Raed abul Ghiyan’s clan has been squatting for fifty years, so the father of two picks up his mail at a post-office box several kilometers away, in the government-sanctioned city of Hura. One afternoon in 2004, while sorting through a small stack of envelopes in his car, abul Ghiyan, who is thirty-four now but looks older, spotted one that stood out—green print, perforated edges, and the familiar return address of his military unit’s liaison office. It was his tzav giyyus, the annual order to report for reserve duty. Into their forties, most Israeli men are required to spend between two weeks and a month of each year in the reserves; abul Ghiyan had been a soldier in the Desert Scouts Brigade, and the tzav giyyus meant he would be heading back shortly for his yearly military stint.

Back at home, his wife stopped him before he could tell her what had come in the mail. “Take a look at what’s stuck to the door,” she said. He’s recounting this to me while we recline on thick, embroidered pillows in the courtyard between his house and one belonging to his parents. A gaggle of young children runs noisily past, and abul Ghiyan, who keeps his thinning black hair brushed forward and thickly gelled, calls his kids over to say hello.

“So I go to the door,” he tells me when they’ve run off again, “and pasted there is a tzav harisa—a destruction order.” By order of the Israeli government, abul Ghiyan’s house would be destroyed in thirty days if he didn’t first tear it down himself.

“I started laughing,” he says. “I held the reserves order and the destruction order up next to each other and laughed. I was in shock a little. How can this be? That in one day I got both of these?”

The irony of his situation is made even more acute by the fact that, in 1954, his family was relocated to the spot it was about to be uprooted from by Israel’s military government. “They destroyed our houses near Shoval and forced us to move here,” he says. “Then they gave my grandfather a gun and said, ‘Guard the border against Jordanian incursions.’ They wanted us here as a line of protection from the West Bank.”

In 2004, he says, the government decided to uproot the family again, this time to make way for a new Jewish village. “Instead of Umm El-Hiran, they want to call it just Hiran,” abul Ghiyan says. “A person volunteers to serve in the army, and this is the gift he gets?”

In the days after receiving the destruction order, abul Ghiyan says that he appealed to officers in the army, to members of the Knesset, to government ministers. “Until the story got into the media, none of them had answers,” he says. “But when the story got on television, newspapers, radio, then their behavior started to change.” After several weeks of protests and appeals, the Israel Land Administration issued a stay on the demolition. Seven years later, the stay holds—and the fate of the village continues to hang in the balance.

Meanwhile, abul Ghiyan waits, raising his children in a home that may not be there in three, six, eight months. And while he waits, he does his annual reserve duty.

* * *

From as early as six or seven years old, Bedouin boys learn that the earth is everything. Sent into the field to graze their family’s livestock, young Bedouin find themselves faced with safeguarding their families’ entire livelihoods. This, it turns out, provides them the perfect training for life as army trackers.

“As kids, we didn’t know what a computer was,” Lt. Col. Majdi Mazareib, chief tracker of Israel’s Northern Command, tells me in an office so spare it’s clear he rarely visits. With his bald head, dark skin, and intense bearing, he could have been mistaken for a pharaoh in another eon.

“We walked barefoot sometimes; most of the time, maybe,” he says. “You survive in the field. You don’t have any limits. You don’t have a Polish mother who calls you in at one o’clock and says, ‘Come eat.’”

As far back as he can remember, Mazareib hunted. He built traps to catch birds for his family. He learned how to raise bees. “The minute you go out into the field, you hear the noises, you touch the plants, you touch the rocks. It’s not a formal course, not like your parents send you to a class. It comes naturally,” he says. “At the same time we had a herd of sheep, and for part of each year we’d go down into the valley with them. We’d be in the fields of the Jezreel Valley for months. We slept in a tent. When you go out with a herd, you’re a leader. Imagine a Bedouin boy, eight years old, his family’s business placed in his hands. It’s a lot of responsibility. You have to make sure the herd eats properly, drinks properly, that you don’t lose any. Now, what’s the connection between being a shepherd and a tracker?”

Mazareib’s cousin and assistant, Dayan Mazareib, comes in and pours us sweet tea. They have an easy rapport, and it’s easy to picture the two of them out in the field together, trying to occupy themselves through long months of boiling days. Mazareib turns back to me.

“It begins with the fact that while you’re watching the herd, your friends come and you start playing with them,” he says. “While you’re playing, you’re not paying attention, and the herd keeps going, and you lose them. Then you have to search for them—and that’s when you start developing the senses: to run, to search, to know. That’s a kind of tracking. And that can be suitable for the army.”

Jewish soldiers describe Bedouin trackers as wizards of a sort. Oftentimes, a tracker can’t point to exactly what it is that has raised his antennae; it’s just a sense. In other instances, very specific signs lead to a particular discovery. Soldiers regale me with stories of trackers who, having spotted a series of footprints etched in the border sand, go on to (accurately) tell their officers how many people have infiltrated; how old they were; how much they weighed; whether they were men or women; and, in some cases, that one had a limp, or was pregnant. Some infiltrators wear specially fitted shoes that slip on backward, so it appears they are leaving Israel rather than entering; trackers can spot this ruse with ease, much as they can tell when an infiltrator has fastened sheepskin to the soles of his feet in an effort to leave no discernible prints at all.

Mazareib tells a story about would-be terrorists caught crossing into Israel from Egypt. Under interrogation, the men admitted that they had been most worried about covering their footprints, citing the IDF’s trackers as their greatest concern. “If they see four Jeeps, it doesn’t frighten them,” Mazareib says. “But if they see one tracker, following their tracks on foot, that drives them crazy. You can neutralize every piece of technology eventually. There’s no replacement for a tracker.”

Trackers also die in higher proportions than other soldiers. When they are working with a combat unit, they travel at the front, ahead of the other men. “The fact that I’m at the head of the force, if I go with the naval commandos or Sayeret Matkal”—an elite recon unit—“that means I’m no less good than they are,” Mazareib says. “There’s sometimes a price, when an explosive is detonated, or there’s sniper fire and trackers are killed. But there’s also an advantage. If I trust someone else to go ahead of me, he can lead me into mines, and I can be killed then, too. So I prefer to go at the front.”

In his ethnography of the Sinai Bedouin, Joseph J. Hobbs suggests that “one reason for the retreat of pastoral nomadism is that non-nomads do not understand how Bedouin live and view life. This ignorance is a source of fear and repression. Rather than try to change the nomads, sedentary powers-that-be might, with more understanding about the desert people, benefit from the detailed knowledge and extraordinary skills that Bedouin have acquired through ages of habitation and experience in the wilderness.” Say what you will about an Israeli-government policy that looks to push Bedouin into cities, ignoring hundreds of years of history. The army does just as Hobbs suggests—respecting the Bedouin’s native skills and putting them to good use. Perhaps this is why the Bedouin I meet who are currently serving in the army seem so much happier than those who have already been released.

* * *

The Druze have had an easier time integrating into Israeli society, inside the military and out. At least, this is the conclusion one might draw from talking to Amal Nasser El Deen.

I go to see the former Knesset member, who is now eighty-three, in his office at the Yad Labanim Druzim, a memorial to Israel’s 369 fallen Druze soldiers in the village of Daliyat al-Karmel. He sits behind a large wooden desk, with photographs of Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and President Shimon Peres hanging over the Israeli flag on the wall behind him. Nasser El Deen is a Likudnik: a member of the right-wing party of Netanyahu, Menachem Begin, and Ariel Sharon. When I suggest that, as an Arab, his membership in this particular political organization sounds odd to Western ears, he laughs—when he was in parliament from 1979 to 1988, he says, half the party spoke Arabic. It was the political home of Jewish immigrants from Morocco and Yemen, from Iraq and Syria and Algeria. This isn’t my point, and he knows it.

But Nasser El Deen wants to talk about his son. Lotfi Nasser El Deen was killed in action in 1969, while Amal was on the road between his home in Daliyat al-Karmel and a meeting in Tel Aviv.

“At the same hour Lotfi died, my body became paralyzed,” he tells me. “I stopped my car and sat on the side of the road for half an hour. I couldn’t go forward. I had no strength. So I turned around and headed back to my office in Haifa. After half an hour, the town major of Haifa and the Druze unit officer arrived, and they sat down across from me at my desk, and they just looked at me. And for several moments they didn’t speak. I said to the unit commander, ‘I know something happened. I have two brothers in the army, and I have a son. So tell me what happened.’ He said to me, and he was crying, hard, ‘Lotfi is no longer with us.’ I said to him, ‘What happened? I talked to him last night. He said he was coming home.’”

The day Lotfi Nasser El Deen died was to have been the day he was released from the army after five years of service. But while returning his equipment to a base near Tel Aviv, he got word that a terrorist cell had crossed the border from Jordan, near the Great Rift Valley. “He refused to return his equipment,” Nasser El Deen tells me. “He told his commander, ‘I’m getting a force together for an operation.’ And he did. He went at the head of the force, and they got to a particular spot, and the infiltrators opened fire on him and he was killed. On the last day of his service. He was twenty-three.”

Nasser El Deen unscrews the lid on an orange coffee pot and pours us each a small cup of what Israelis call botz, mud. After a few moments of contemplative quiet, he continues. “It was very hard to hear this,” he says. “But I knew that if I was weak, I would damage the funeral and my son. You know, the next day at the funeral there were thirty thousand people—thirty thousand!—who came from all over the country. It was the first time that the minister of defense, Moshe Dayan, appeared at a soldier’s funeral. His aide approached me and said, ‘Excuse me, Amal, I’m very sorry. I need to bother you for a minute.’ I said, ‘Go ahead. What’s happening?’ He told me, ‘On Syrian radio, they are singing and joyful because they say Moshe Dayan killed your son. And they’re saying that this is the fate of any person who respects the Jews and stands together with them.’”

Nasser El Deen takes a sip of his coffee before he goes on. “Here’s Amal Nasser El Deen, they were saying, Druze, former soldier, a well-known public figure. His son was killed at the hands of the Jewish defense minister. So I called over the Israeli radio and TV people and I gave an answer. I said to the Syrians, ‘You can sell your lies on the street of Damascus. Your lies won’t work with us. Moshe Dayan and I are brothers. Here he is, sitting at my side.’ The whole world saw this.”

* * *

“A lot of Druze will tell you, the Jewish people and us, we’re partners, etc., etc.”

Rafik Halabi, a well-known television journalist and an “utterly secular” Druze, sits in the high-ceilinged office just off the entrance to his attractive home, which is also in Daliyat al-Karmel. Behind him is a bookshelf stacked neatly with videos and DVDs of reports he’s filed over the years—on politics, on religion, one on the transmigration of souls, a central tenet of Druze faith. Beside the shelf is an editing suite, and over his shoulder is a photograph of Halabi with Israel’s first Druze combat navigator, a young man whose face is obscured by the tinted visor coming off his flight helmet. Halabi’s house is just a few short blocks from Nasser El Deen’s office, but when they talk politics, the ideological distance dividing them seems almost interplanetary.

For many years now, Halabi has been a vociferous critic of Israel’s policies toward its Arab citizens. His complaints, issued in TV news reports, newspaper columns, books, and documentary films, are remarkably similar to those I hear from the Bedouin. We are second-class citizens. They promise that military service will help us advance, and it doesn’t. The state appropriates our land with impunity. And once we’re done serving in the army, there are no jobs.

In recent years, Halabi says, Road No. 6, a new north–south toll road; the Beersheba–Nahariya train line; and a gas pipeline have all been built on land taken from the Druze community. The same goes for the city of Yoqne’am, a center of Israel’s thriving high-tech industry. “Yoqne’am?” he says. “It’s fantastic. Congratulations. Now, ninety percent of that is built on the land of Daliyat al-Karmel.” In the 1950s, Israel paid local Druze “peanuts” for that land, Halabi says, and proceeded to seed it with a series of military installations. Later, the army camps were razed to make way for Yoqne’am.

“They took down those camps and instead of giving the land back to the Druze, they gave it to the contractors,” Halabi says. “I say to myself, ‘So, you did that. Now give fifty percent of the municipal tax to Daliyat al-Karmel. Give twenty-five percent to Daliyat al-Karmel. And let’s say you built a hundred factories there? Build ten factories in Daliyat al-Karmel. But the state doesn’t even see you from half a meter away!”

Halabi believes that Israeli Arabs get shortchanged in these situations because many of the relevant land-use institutions are not government institutions at all—they’re offices founded specifically to serve the Jewish people. “The Israel Land Administration, the Jewish Agency, the Moshav Movement, the Jewish National Fund,” he says, ticking off the list of groups. “These are not institutions of the State of Israel!”

Daliyat al-Karmel’s streets are narrow and labyrinthine, but they’re clean and well paved. And Halabi, for his part, has reached the pinnacle of his profession, working as a reporter and editor at the top networks in this news-obsessed country. He holds a college degree, and was an officer in the army. It looks to me, I say, like he and his neighbors are faring pretty well for second-class citizens.

“That’s true, in comparison to the Bedouin,” he says. “But not compared to Timrat.”

Timrat is the nearby Jewish town where I’ve been staying with family friends. Its residents are well-off high-tech entrepreneurs, businesspeople, air force pilots and other military officers. Ask Timrat’s residents about how the Arabs in Israel are treated and, after telling you what a shame it is that their neighbors aren’t treated better, they’ll say: Still, it’s much better for them here than in Syria. Or, You know, I can’t just put an addition on my house without permits. If I do, the city will come and knock it down.

In many ways, these arguments are true. In January, for example, Civil Administration bulldozers, accompanied by officers from the Border Police, demolished three illegally built homes in the West Bank Jewish settlement of Havat Gilad. One of those homes belonged to an ultra-Orthodox soldier named Shimon Weisman. “Even in my worst nightmares, I never imagined that while I was putting my life at risk in order to defend the homeland, policemen and soldiers would sneak in and destroy my house,” Weisman said afterward.

The quality-of-life argument is worth acknowledging, as well. A recent survey, taken before revolution spread across North Africa, ranks Israel’s standard of living as the forty-seventh highest in the world; the nearest Arab nation on the list is a pre-revolution Tunisia, coming in at number seventy-seven. Arabs here vote for their leaders, which, as yet, citizens of many Arab nations cannot. Israel’s health-care system is also far better than just about anything available elsewhere in the Middle East; Arab presidents have been known to sneak into Israel under assumed names for specialized medical treatments.

But that, Israel’s Arabs say, is like comparing apples and oranges. Because Arab Israelis don’t judge themselves against the rest of the Arab world. They judge themselves against their neighbors.

* * *

When Amal Nasser El Deen’s second son was kidnapped by members of Hamas in 1996, the army, the Mossad, and Shabak went looking for him in the West Bank. Saleh Nasser El Deen had recently finished his military service, and, taking advantage of what felt like a new openness in the aftermath of the Oslo Accords, he headed off to the Palestinian territories for a short visit. The Israelis never found a trace of him after that.

When an Israeli is kidnapped, it is very, very big news. Stories about Gilad Shalit, the Israeli staff sergeant kidnapped by Hamas in 2006, appear in Israeli newspapers nearly every day. Signs proclaiming that gilad is still alive adorn cities and towns across Israel. Shalit’s parents have become national figures, permanently manning a tent in front of the prime minister’s Jerusalem residence to keep their son’s fate constantly in the government’s sight lines. On Shalit’s birthday, in August, I get caught in a traffic jam when hundreds of supporters descend on the tent to stand with the Shalit family in demanding that the prime minister trade hundreds of Palestinians currently held in Israeli jails for Shalit’s safe return. A few days later, while driving from Timrat to the nearby Memorial for Fallen Bedouin Soldiers, I hear the host of a pop-radio station go to commercial by announcing how many days Shalit has been imprisoned.

“So why do we hear so much about Gilad Shalit and nothing about your son?” I ask Nasser El Deen now.

“Because I’m certain that my son is no longer with us,” he says. “Which is different from Shalit, who is alive.”

“Why are you certain?”

“My son is Druze. And they don’t like the Druze in the West Bank. Hamas is harsher in the case of a Druze. They don’t like us. They say we’re traitors. We say different. But I’m sure, almost sure, that they executed him.”

Twelve years later, Amal Nasser El Deen’s grandson was the first Israeli casualty of the 2008 war in Gaza, killed near Nahal Oz when a Palestinian rocket exploded beside him. His name was Lotfi, after his uncle, the first of Nasser El Deen’s sons to die.

* * *

Rafik Halabi: “Let’s talk for a minute about whether or not it’s good for the Druze to get drafted. Maybe on the individual level it’s good. Maybe it’s even good for the community. But on a gut level, do the Druze get satisfaction from this thing? I’d say no. Really no. Now, many Druze will tell you: ‘What are you talking about? We’re Israelis! We’re Zionists! This is our country!’ Nationalist speeches. But I’ll tell you about the youth. I’ll tell you about my second son, who was in the army. What did it leave him with? Was it important to him? It’s not important to him. He knows that the civilian problems of the Druze are so intense, so painful, so difficult—land problems, infrastructure problems, budget problems, relationship problems—that they raise questions about the draft. More than ninety percent of ultra-Orthodox Jews don’t serve in the army, and their political power gives them more rights than anyone else in the country. The equation of obligations and rights is an equation that does not exist.”

* * *

On July 27, 2010, the same day that Faisal abu Nadi invites me into his home and offers a debatable account of the destruction of his village’s “clubhouse,” I go to see El Arakib, the Bedouin village that the ILA has just demolished. Israel says the village is illegal; El Arakib’s residents point to their nearby cemetery and say they’ve lived there for decades. The competing claims have been making their way through the courts, and a government source tells me that it was a court order that finally allowed the demolition to go forward. The residents of El Arakib, though, insist that the case was still being adjudicated at the time the bulldozers moved in. Either way, it bears noting that Israel didn’t touch the cemetery, though presumably it, too, was illegal.

I spend the better part of an hour wandering around the ruins. Piles of corrugated metal, iron bars, and concrete rise like boils on the back of a dust-covered hill. Dozens of pigeons roost in the scattered remnants of their coop. Bulldozed trees lie on their sides, roots jutting into the air like a dead dog’s legs. Piles of hay smolder.

Meanwhile, a few village men are hammering together a wooden frame for a new tent. Once they’ve covered it with a black tarp, I approach and ask where I can find the village sheikh. They point me to a small olive grove that remains standing near the foot of the hill, and I walk over and ask the sheikh, Sayah al-Touri, if we can talk.

He’s in a gray robe, a white turban, white cotton pants, and dusty black loafers, and has an imposing white mustache. He displays none of the vaunted Bedouin hospitality when I appear, but then again, as of this morning he doesn’t have a house. I crouch down next to him, trying, pathetically, to match his position: feet flat on the ground, knees bent, butt dangling an inch or two above the dirt.

“The Nazis that they talk about?” he says. “They didn’t do the kinds of things that they did to us today. They say this place isn’t suited for Arab settlement. It’s our land! We will continue to build! We are already building!”

A group of local men begins to assemble, just listening at first, eventually launching into a little call-and-response exercise.

“This land is the land of our fathers and our grandfathers,” al-Touri says. “Three hundred and fifty people live here. We have been living here for a hundred and ten years!”

I ask him if he or any of the men in his village served in the IDF.

“It’s no honor for me to serve,” he says. “This government is not a government that gives anyone respect. Do you think they wouldn’t have destroyed this place if we served in the army? Is that what you think?”

I realize, after a long pause, that it’s not a rhetorical question. I tell him I don’t know.

“First of all, they destroy soldiers’ homes,” he says. “Even officers with two stripes!” The group of men starts getting animated.

“Paratroopers!” one yells.

“Trackers!” another shouts.

The sheikh, meanwhile, goes quiet. He just stays where he is, crouching, staring at the ground, while the men around me talk over each other. My thighs are on fire, shaking embarrassingly. I can’t hold this position any longer, so I stand up. The sheikh stays where he is; he’s been forced to move once today already.

* * *

A week after I visit El Arakib, Israel returns and destroys whatever the villagers have rebuilt, including the twice-demolished home of forty-six-year-old father of three Abu Madyam Kayid. When I return the next afternoon, I find Kayid sitting on a milk crate, smoking, in a tent he’s just finished putting up. His wife comes by with a kettle of tea and wordlessly pours a paper cup for each of us.

“We started building after they left, in the evening,” Kayid says. “As sure as we are that they’ll destroy this again, we’re sure of ourselves—we’ll keep on building.”

I tell him I was here the previous week, when the village was razed the first time. “I spoke to the sheikh,” I say. “He told me that guys from this village don’t serve in the army—that it’s no honor to serve a country that would do this to its citizens.”

Kayid thinks a minute, removes his leather cowboy hat, mops his brow with the back of his hand. “There were two guys,” he says.

“What happened to them?” I ask.

“It wasn’t pleasant for them to live here, so they left.”

“Where did they go?”

“Rahat,” he says. Rahat is one of the cities Israel established for the Negev Bedouin.

“And it wasn’t pleasant for them why?” I ask. “Because the others here didn’t approve?”

“Right,” he says. Then he climbs onto a tractor and invites me over to see the rubble where his house once stood. El Arakib has since been destroyed, and rebuilt, nineteen more times.

* * *

There was no requirement, under the initial court order authorizing the destruction of El Arakib, that the Israel Land Administration return to raze rebuilt structures. Still, subsequent demolitions didn’t actually require a court order—a more easily obtainable administrative order from the ILA sufficed. “That’s a stupid act, to go destroying it back and forth,” says a government source. “The government had to knock it down because the court ordered it. But after the first time, that’s it. They made El Arakib a symbol. I don’t think it’s smart.”

It is one of many symbols that observers and the Bedouin themselves say may spark a third intifada—this time emanating not from Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, but from the Bedouin citizens of Israel proper, if not their fellow Israeli Arabs.

“There may be something that happens that ignites them,” says Clinton Bailey, the Bedouin scholar. He notes that the First Intifada was sparked by a single car accident in Gaza, and the second erupted after a visit by Ariel Sharon to Jerusalem’s Temple Mount. This time around, he says, it could be further home destructions, or even an unpopular decision from the panel working to bring the Goldberg Committee’s findings in line with government thinking. “There’s a very good chance that they’re going to offer things to the Bedouin that the Bedouin can’t accept,” Bailey says. “All I can say right now is that the tinder is there.”

Of course, it’s also possible that the committee on the Goldberg Committee will produce a proposal that manages to satisfy all parties involved. In June 2011, this second panel, known as the Prawer Committee, issued its recommendations, which included relocating some thirty thousand Negev Bedouin to expanded authorized areas around existing government-planned towns such as Rahat and Hura, and offering these transplants compensation in the form of money and land. As soon as details of the plan were released, influential Bedouin came out against it. The cabinet was set to approve the recommendations in mid-June, but strong opposition forced a delay. At the time of this writing, intense behind-the-scenes wrangling is underway to forge some sort of consensus, but no one involved is overly optimistic.

Even among those who anticipate an outbreak of public opposition, though, the form it will take is another question. Will it be violent, like the October 2000 riots in which a dozen Israeli Arabs were killed in clashes with police? Will it resemble the protests that succeeded this year in Egypt and Tunisia, and may yet elsewhere in the Arab world? Or will the dimensions of an uprising be less clear?

“Intifada is a generic term,” says Moshe Arens, the former defense minister. “There’s a lot of crime out there. A lot of stealing. A lot of poaching of the property of Israeli farmers. A lot of traffic accidents. If you want, you can call that intifada. It’s a reflection of the social conditions of most of the Bedouin population here.”

The Bedouin identify primarily on the basis of tribe and clan rather than as a larger community; they lack cohesiveness and a unified leadership. Further, desert life has made them patient sufferers, for better and for worse. If, however, they do rise up, the soldiers among them—charged with protecting the state from disturbances of this sort—may well find themselves in an untenable position.

A few weeks before leaving Israel I meet with Eli Atzmon, a longtime military-intelligence officer and onetime head of the Bedouin Authority, a position that put him in charge of enforcing house-destruction orders. Now a private consultant to Bedouin making land claims, Atzmon’s views are frequently sought by Israel’s political leadership. Like Arens, he believes that the army can be a great equalizer—but says the problem goes much deeper than anything the military can fix on its own.

“It’s true that the minorities today can go to more places in the army than before, but that’s not enough,” he says. If Israel continues along its current course, Atzmon tells me, its growing Arab population will begin to see the Jewish state as inevitably set against them. “A little boy who is awakened at five in the morning and sees a large force next to him and sees that they’ve destroyed his house—he doesn’t know how to do the math,” he says. “Justified? Unjustified? The government? The law? It doesn’t interest him. They destroyed his house. He’ll remember that for the rest of his life.”

Here Atzmon pauses for a moment and scans his tiny office, which is lined with maps of Bedouin settlements and file boxes labeled with the names of tribes and villages. These documents are the tools with which Israeli Arabs have attempted to lay claim to their homes; the tools Atzmon hopes to use to help repair a badly broken situation. Eight months after we first meet, the government approaches Atzmon in hopes that he will agree to persuade the Bedouin to get on board with the Prawer Committee’s plan. He doesn’t immediately sign on, insisting that the committee first give the Bedouin themselves a hearing. That doesn’t happen. Instead, Atzmon is now pushing for significant changes based on what the Bedouin would have said, had they been invited to speak. Whether or not these changes will be made remains unknown; the latest effort to solve the Bedouin land problem is poised at the edge of a precipice. But the status quo, Atzmon says, will serve no one.

“You can’t go around destroying houses and think that it will all pass quietly,” he tells me. “The Islamic Movement is waiting in the wings. Everything together boils, boils, boils. And in the end it will explode. And whoever doesn’t see that is either blind or doesn’t want to see it.”

Chanan Tigay has contributed to publications including Newsweek, New York magazine, the Wall Street Journal, and the San Francisco Chronicle. He has covered the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a correspondent for the Jerusalem bureau of Agence France-Presse.